Being (in the midst) of two. Interstice and deconstitution in cinema and architecture

2012

“Not knowing the way out or the way in, wonder dwells in a between, between the most usual, beings, and their unusualness, their “is.” It is wonder that first liberates this between as the between and separates it out. Wonder −− understood transitively −− brings forth the showing of what is most usual in its unusualness. Not knowing the way out or the way in, between the usual and the unusual, is not helplessness, for wonder as such does not desire help but instead precisely opens up this between, which is impervious to any entrance or escape, and must constantly occupy it.”[1]

“We are human beings because we are outbound (en partance), disposed towards a departure about which we can and must know that no definitive arrival is possible or promised. It is in this impulse (elan), in the obligation of departure, since we cannot do otherwise, and in this risk-taking (prise du risque), in the wager of departure, that we can live a life worth living.”[2]

The story I wished to put to you today is simple. I wanted to begin with the beginning of architecture, which is also the beginning of the possibility of life – that is, the interval which makes space and time possible, which gives us room to be and to breathe. I wanted to extend this sense of the interval into a common trope, commonly misconstrued – that is, duality, the duality between the interval and the walls it spaces-out. In other words, the duality between the limit and the limited, or in architectural terms, between inside and outside, private and public. I wanted to suggest that this duality does not – logically, factually or existentially – exist.

Duality arises from the incapacity to hold two conditions simultaneously – light and dark for example, grief and humour or self and other. As such it arises when time is conceived diachronically or chronologically as a succession of instants. Classical narrative, whether cinematic or spatial/architectural, is founded on the disassociation, in sequential time and linear space, of what is coincident and synchronic. If duality is recast as a condition of being-two, that is of being-simultaneously-dual – private and public, inside and outside, on screen and off screen, now and then, here and there, virtual and actual – then what first appears to be ambiguous in its oppositional indeterminacy turns out, for a moment, to eclipse the antinomical in favour of something more complex, indistinguishably inter-folded or inwardly-concatenated.

Beings and worlds are folded, woven or felted out of beings within beings, worlds within worlds, scales within scales and rhythms within rhythms. As such they are states of what Gilbert Simondon called surfused or supersaturated metastability that take their fabric (psychosomatic, filmic, tectonic) to a threshold of crisis where two things happen: the fabric reaches a limit of compaction or intensity and it begins to dilate and unravel. This unravelling produces a new state or emergent condition that could not have been planned or predicted. The function of a work (a text, a film, a building) is to frame and provide situations in which such emergence is enabled to take place. Such framing and providing is a matter of care or solicitude. It is properly speaking a technics, a manner of doing something and the know-how that attends to it, a mnemotechnics that is also mnemoethics - a watching and waiting, being-with and being-for that solicits the coming-into-presence of something: a mood, an atmosphere, an emotion, an insight, an exchange, an idea, a project, a melody, a word, a phrase, an expression, a recollection, a person, a place. This is what any work (text, film, building) is made-for.

Entr’acte: in medias res (in the midst of things)

Jean-Luc Godard contends (via Virginia Woolf) that cinema exists and is thinkable only in the intervening sequences between shots and acts—in the entr’acte, the interval, the intermission. Cinema is therefore an art of the interstice. Its proper sense does not emerges in a scene as such, but in its transition to other scenes or shots, whether through long sequences, cuts, superimpositions or transpositions—that is, in the passage and passing away of the image; and in the jointing and connecting of those images and traces, that is, in technology (techne) or art.

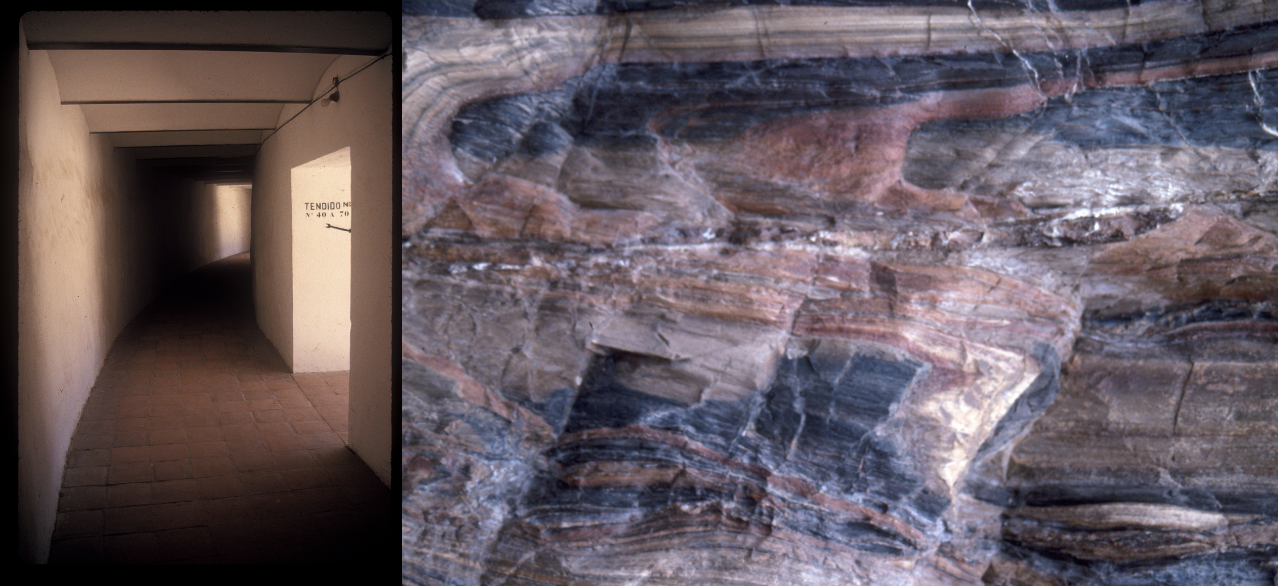

The in-between is neither void nor neutral. It is a terrain with a topography that can be charted and investigated. The milieu is not an intermediate terrain vague, an empty pause or chasm - it is itself a world, or a whorl of world within worlds. The mythological tradition is full of such intermittent middle-places – Midgard (middle-yard/enclosure), Mittelerde (middle-earth) and Greek oikomene (ecumene) all refer to the intermediate world of human existence, poised between giants and dwarfs, gods and demons, heaven and hell… In-be-twixt, to be two, to be radical ambiguity: the interstice stands as a zone of indiscernibility that is simultaneously present and absent, that separates and affords access between regions or yields passage through into other dimensions and worlds. This deterritorialising capacity of the interstice produces the radically uncanny. In the interstice, and in the interim, architecture encounters the strange and irremediable catastrophy of its own deconstitution.

Deconstitution or deconstruction are fundamentally process that take place at the joints — where analysis loosens (Latin: ana-lusis = to loosen apart) and liquidates the knots that constitute an assemblage. Plato refers to the dismantling of a chicken carcass—not by hacking away at it indiscriminately, but by working into the gap/weakness at the joints and levering these knots open to separate its components. The shuttle has the same function in weaving. It moves in the gaps and interstices of warp and weft, infiltrates the hollows and fuses or names-together-across (diakrinomen) warp and weft into an interconnected network to weave (sumploxe) the fabric. Significantly, the joint is a site of both strength and weakness—a pivot of assemblage and disassemblage, construction and destruction, creation and catastrophe.

Whorls of worlds

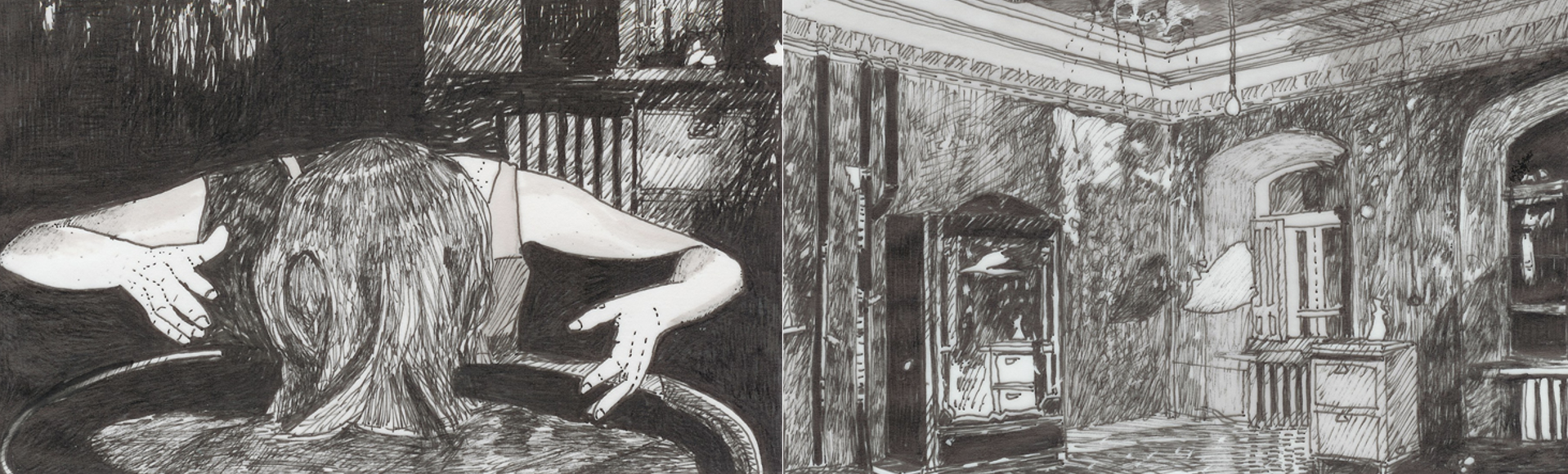

I would like to interpret a sequence from Andrey Tarkovsky’s 1979 film Mirror in line with the main narrative I am relaying, proceeding from the deconstitution of the subject, of space and time through intensification and crisis to emergence and solicitude. By a systematic building up and conjugation of images that function like resonant metaphors, the film achieves such an intensity of overlay that the coordinates and logics of space and time become undecidable and fold into complex worlds within worlds. Simultaneously, the compaction of images and metaphors, paralleling an overlay of reminiscences for the narrator, densify the semantic materiality of the image to such a degree that its consistency begins to develops fault lines, to falter and threaten collapse. In this extraordinary sequence, the narrator remembers himself as a child before his mother’s dressing table mirror. As he looks into it the scene shifts to the past and his young mother, washing her hair, framed within a dark space glistening with reflections from oil-black walls, wet hair and clothing, and mirrors dissimulated into the background. As she stands dripping the entire room begins to weep water from all surfaces and collapse. The scene then shifts to a dark room, presumably the same room at a later time, in which the author’s now elderly mother approaches the glass. The mirror doubles a window set alongside it, suggesting a black night outside. It is unframed and so does not read as an opening in a wall like the window beside it, but as pure surface and pure aperture.

Its position in the room is ambiguous and it appears suspended in space rather than fixed to the wall. It has a transparent immateriality yet reflects multiple overlaid images—a painted twilight landscape of clouds, earth or sea, tree and open fire; reflections of a ceiling cornice and floral wallpaper patterns in the room behind; images of the remaining cornice and wallpaper behind its surface; a floating plane, like a table that reinforces the threshold; reflections of the arched window and the mother slowly nearing the mirror’s surface, as if from its other side. She raises her hand and places it on the glass. This gesture not only validates but produces the duality of the two sides and the filmic boundary that separates them. She looks into the mirror as if questioning the materiality of its surface, as if it were on the verge of yielding and giving access to the multiple spatialities and temporalities of memory. The surface of mirrors operates in several ways but always as a cipher of cinema itself. It is a filmic screen onto which images are projected—but from both directions, and exchanged into both of the spaces that front onto its surface. It is a frame which delimits and veils compossible worlds; a translucent doorway connecting places and times; an apparatus of memory, recollection and projection and a surface of monstration.

The collapse of the room marks a crisis in the concrete reality and existential milieu of the scene. The actual time of the sequence is left ambiguous since multiple temporalities are simultaneously fielded. There is clearly a looking back to the author’s childhood in the early scenes. The old mother might herself be looking back, looking forward, returning from the dead or returning to meet her younger self. The question is less a matter of conveying chronological accuracy than of showing the circulation of real and imagined, actual and virtual, remembered and projected places, times and events within a single setting made possible by and within this interstitial rupture. The implausibility of the event amplifies this condition of crisis, enabling the images to convey more realistically what an experience of this rupture might feel like. It is not only the room that collapses but all the spatial, temporal and subjective coordinates of concrete existence. The moment triggers a disorientation in the subject and an avalanche of images which had welled up, to only now break through the resistance of forgetfulness—just as water violates the architectural skin and takes with it all guarantee of stability, shelter and safety. The sequence works metaphorically to convey, through a monstrous architectural catastrophe, the exposure of consciousness to a surfeit of the repressed memory and potentiality of the subject.

Mnemotecnics

These instances parallel a constitutive condition of remembering, a defining characteristic of the apparatus of memory: that remembering and memorialisation - or monumentalisation since the idea is cognate - is not a matter of attaining or guaranteeing accurate or even adequate reminiscence. Rather, it is fundamentally about making a place for the difficulty and impossibility of remembering; a space in which we can be with memory as it fades and withdraws or evades our grasp, and yet remains just there, on the tip of our tongue; an experience of that moment betwixt remembrance and forgetfulness when a memory withdraws into oblivion at the same time as it presents itself with the highest certainty of delineation.

Memory is poised on forgetting and remembrance is in fact the iterative, rhythmic play between appearance and disappearance, recollection and oblivion, presence and absence. This is why the proper field and operation of memory is not conditioned by the antinomy of light and dark, but the gloaming—an ambiguous and precarious, interstitial condition or shade of darkness wherein delineations fluctuate and become indeterminate. The experience might be like awaking from a dream that, at the same time as it is present to us as sharp recollection, fades and withdraws into uncertainty. Each time we try to remember, the narrative is dismantled into incoherence. Or the experience might parallel one’s presence and attentiveness to the systematic withdrawal of another in death; of one who is palpably present and with us while simultaneously fading and absenting themselves. Such moments require delicacy and care. They call for a kind of disengaged solicitude that watches, wakes and waits; that cultivates a countenance of being-with and being-for whatever eventuates. This is the ethical power of the interstice that architecture remains to confront.

To accommodate or furnish a space for this calls for a technics of resistance where the materiality of the field we happen to be working (in) – light, time and narrative for cinema; space, time and materiality for architecture; the gravity of thought and the weight of words for language – plays an impressive, constitutive and formal role. I want to make the point that the workings of memory are not virtual or insubstantial, they are deeply and intricately material even as the traces they leave seem evanescent. As Lyotard notes, after Bergson, “mind is matter that remembers” its origins, interactions, transactions and immanence[3] – a reading supported by the common linguistic basis of an extensive lexicon: human, man, mind, mnemonic, memory, memorial, monument, moon, month, measure, metre, matter and mother, through the etymons *MEN = to think and *MA/ME = to measure, weigh up, consider, reflect.

That is to say human being is fundamentally mnemonic and recollective (Greek: anamnesis = without-forgetting). Photography and film might be the preeminent arts of recollection, but cinema differs in that it shows the traces of memory passing, it shows the process of its withdrawal and erasure into oblivion. With cinema we witness time and all that it conditions pass us by and depart from us – personalities, families, communities, peoples, narratives, histories, landscapes, creatures, emotions, melodies, airs, tones, rhythms, beats, ideas, theories, phrases, words, voices, whispers… These all have material being and they affect and impress us materially. Consequently we are ourselves mnemotechnical. To use Bernard Stiegler’s phrasing we are retentional apparatuses that register and record the passage of what has passed us by. We are archives and museums, laboratories and studios of recreation and renewal.

Since architecture is fundamentally a technical undertaking, assuming techne = know-how, making, art, then the key function of architecture must be to operate as a mnemotechnical apparatus or infrastructure which tracks, frames and unclenches traces and recollections – of self, of place, of moments, of encounters. How might architecture do this?

Following his assertion that the proper concern of cinema is not to “realistically” convey the factuality of events but to capture their reality, Tarkovsky makes a telling observation about the way imagination, dreams and recollections can be conveyed in cinema:[4]

“How is it possible to reproduce what a person sees within himself, all his dreams, both sleeping and waking? … It is possible, provided that dreams on the screen are made up of exactly these same observed, natural forms of life. Sometimes directors shoot at high speed, or through a misty veil… But that mysterious blurring is not the way to achieve a true filmic impression of dreams or memories. The cinema is not, and must not be, concerned with borrowing effects from the theatre. What then is needed? First of all we need to know what sort of dream our hero had. We need to know the actual material facts of the dream; to see all the elements of reality which were refracted in that layer of the consciousness which kept vigil thorough the night… And we need to convey all of that on screen precisely, not misting it over and not using elaborate devices. Again, if I were asked, what about the vagueness, the opacity, the improbability of a dream?—I would say that in cinema `opacity’ and `ineffability’ do not mean an indistinct picture, but the particular impression created by the logic of the dream: unusual and unexpected combinations, and conflicts between, entirely real elements. These must be shown with the utmost precision. By its very nature, cinema must expose reality, not cloud it.”4

For Tarkovsky this is not to be sought in special effects or literal translation, but in the focussed and intensified working of the materials and technologies of film itself, paying close attention to the inherent logic of the moment being conveyed. Cinematographers achieve this quality in very different ways—Tarkovsky (Mirror) by intensifying the material conditions of the image and the time it takes to pass; Nicholas Roeg (Bad Timing) by switching between multiple timeframes with great velocity; David Lynch’s Lost Highway by disestablishing psychic and concrete spatialities and temporalities to produce radically altered, parallel states of being; Carlos Reygadas’ Silent Light by turning the cinematic frame to pure attention and watching-out-for whatever comes; and Jean-Luc Godard (Histoire(s) du Cinéma) by montage which juxtaposes, multiplies and densifies narrative texture.

In every case, the strategies and techniques of manipulating temporality are deployed entirely within the fundamental limits of cinematic production—the 24p frame rate limit of image projection—rather than by adopting practices that lie outside the tectonics of cinema. This suggests that a work will persuasively engage with the real only by intensively working its fundamental limits, rather than by eliminating or escaping them. What implications might there be for architecture of this cinematic eclipse of time within time itself? How might the agency of cinema allow architecture to conceptualise a parallel eclipsing of space within space itself, and how might this deterritorialise architecture, opening it up to the strange and unfamiliar? [5]

Much current architectural theory and practice declares an urgency for engaging with contemporary realities in which certainty and stasis no longer hold, where universals have no purchase, where fluctuation and interminable variation condition experience and where the disconnected and fragmented are commonplace. In response, architects look to formal systems and modes of working which privilege the dynamic and the ambiguous. Attracted to so-called non-Euclidean geometries and rhizomatic networks, embedding design in the diagramming of fluctuations in global markets, political deterritorialisations or other kinds of statistical analyses and parametric modelling, architects look for relevance in the conditions, needs and demands of a contemporary world in a state of crisis. As a result architecture becomes a mimetic and formal representation of the dynamic, fluctuating, unsettled, unpredictable and catastrophic lineaments of that crisis. But doing so it merely trades one form of mimesis—the imitation of transcendent permanent realities—for another: the imitation of immanent impermanent fluxion. It continues to adhere precisely to the literalness that Tarkovsky warned against. It is not a question of finding “elaborate devices” to represent certain conditions or to displace certain accepted modes of working. Rather, it is a question of remaining and working with the foundational and familiar existential characteristics, elements and processes of reality in order to convey its unsettling and uncanny dimensions. The implication for architecture is that the most unsettling, the most unfamiliar and extraordinary experiences happen to take place precisely in the midst of the most ordinary and mundane of circumstances.

An architecture of potential might present itself, formally retrained, calibrated to specific temporalities of engagement and emergence, not expressing the fully formed but rather the inarticulated potential of forms built up and dissimulated within the simple, the homogenous, and the smooth. Its temporality would simply frame a kind of waiting for what comes, a gathering of the minuscule, the small scaled, the episodic, the fine grained, the quiet and the slow. It might frame the everyday in order to register and indicate such things as moments and phases of time, sunlight on soil or leaf, wind in foliage, clouds moving across the sky, sheets of snow and the sounds of human presence. It might be attentive to the passage of time in its minutiae, the receptive character of places, the manner in which they gather memories of the past and projections of the future, the way that the “now” might not be experienced as a solid entity but as pure passage and trajectory. [6]

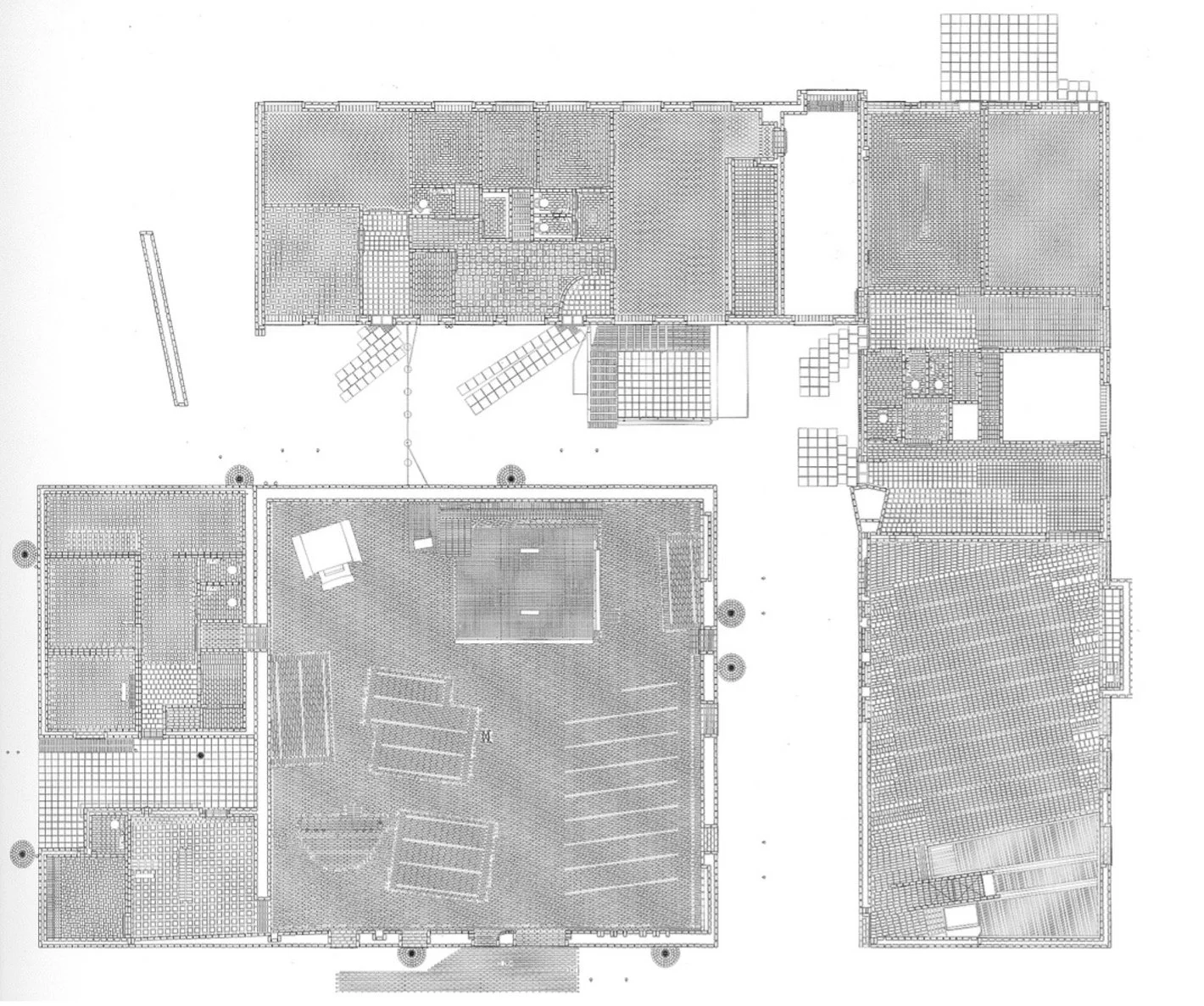

Colin St John Wilson saw something enigmatic in the work of Sigurd Lewerentz,[7] which he explained by citing Lewerentz’ own motto for his work: “Mellanspel”—meaning a playing (spel) between (mellan). The contention is that Lewerentz sets up various antinomical oppositional themes, which he then plays or shuttles-between to create discrepancy, ambiguity, indeterminacy and obliquity. From that result a sense of enigma and unexplainable mystery that St John Wilson implies might be proper to a sacred building. The discrepancies which Lewerentz plays out in the geometry and materiality of St Peter do confirm this. The plan is square rather than basilican, therefore centralised rather than linear. In an ideal square no single direction predominates. But Lewerentz carefully and forcefully differentiates between several axes that constitutively bisect the space. The altar is not centralised but located just to one side of the main axis and diagonally opposite the entrance door. This sets up an inherent tension in the space. There are four entrances into the chapel. The two axes linking these doors and the altar form a cross that is unaligned to the cross axis of the geometric centre of the room, or the cross axis through the central column. Consequently the room has three incommensurable crosses that produce a charged space.

Lewerentz works further geometrical alignments, directions and dynamics into the space to contest the apparent simplicity of the square, distort its rational order and install a strange dislocation with tectonic, experiential, theological and liturgical registers. The vaulted ceiling billows in uneven waves due to the alternating pattern of ribs, which expand and contract in plan as well as slope slightly towards the centre of the space from each side. The undulating, folded brick ceiling is read against a pair of deep steel beams that span the full width of the space. These are supported on a secondary beam, almost imperceptibly asymmetrical to the single column that supports it. The column is marginally off-centre within a space that is exactly square. The asymmetry of the column is reinforced by the offset assembly of beams—the two major cross beams also having the effect of countering the orientation of the vaults. This steel assembly effectively subdivides the square chapel into four smaller regions. The altar is marginally offset to the south of the central axis of the room and placed in the quadrant opposite the entry door. The baptismal font is in the quadrant closest to the entry. In both cases this is in accordance with normal liturgical practice. The lectern and organ occupy the third quadrant and the major portion of the congregation occupies the fourth. None of the windows or doors is symmetrical to or aligned with the geometric axes of the whole space, or with the quadrants in which they are located. The combined effect of this highly complex but barely perceptible setup, made of very slight nuanced geometrical shifts and overlays, is considerable.

In terms of directionality and dynamics, the ceiling vaults run west-east towards the altar to emphasize a processional direction. At the same time, they rise from each side to a north-south pitching ridge above the column assembly. The combined effect is to stretch the west-east dimension and to gather, centralise and raise the space upward. This tension between two tendencies holds the space in suspense, in an indiscernible state somewhere between stability and dissolution. In the brick floor the bed joints run north-south, but at an angle to the square plan. Within this linear pattern Lewerentz inserts several areas of paving at other angles—like rugs or patches set within a larger web. Only the paving in the zone of the altar conforms to the orientation of the walls. Despite reading more like a woven multidirectional surface than a linear array, the heterogenous patterning of the floor counters the orthogonal alignment of the overall space and the altar, as well as the walls. The directionality of the paving resists and decelerates that of the vaults. These contrasting shifts in pattern and geometry create disjunctions and incommensurabilities in the spatial order of the room.

The intricate juxtaposition of geometries, spatial directions, tensions and proportions tends to overburden, materialise and condense the space; but also mobilise its materiality, causing it to fluctuate, alternate and oscillate, but in minor, almost imperceptible ways. The tectonic implications exceed any semantic, metaphorical or symbolic readings that could be ventured for the building. The central armature that supports the roof may evoke the cross on Calvary but also zones the space to frame a differentiated collectivity. It produces a distinctive weighty, grave ambiance that matches the simultaneous grief and joy of reflection, prayer and celebration that define the Protestant mass. It turns an abstract spatial structure into a world or a place, calibrated to specific modes of being, being-with-others, and being-with-otherness. Lewerentz does not achieve this through formal complexity, large-scale compositional tropes or unusual geometries. The scale of tectonic endeavor is extremely modest, but every move carries considerable weight and enduring affect. He does not abandon architecture’s foundational tectonic dimensions or remit but crafts the tectonic by subjecting it to significant strain and working at it until it yields.

For Heidegger, the temple results from a work, an operation on matter. This work does not merely consume matter, using it up without residue in the making of a thing, which is the case in equipmental making. Rather, this work—the work of art and by implication the work of architecture—brings the material to presence in a more originary way. It “draws up out of” the material the “mystery” of its “clumsy yet spontaneous support.”[8] As a result of the work, the material comes into its own and also comes into a world—into the openness of the world of the work; in this case of a templum, a place in which the deity presents itself to sight.[9] Matter is enabled and ennobled by art to become more essentially itself, to come to and to know itself for the first time. St Peter is a masonry building. It rests, stands and supports. It shelters a clearing and illuminates. It weighs heavy and its colouring gloams and darkens. But Lewerentz takes his working of the material to an entirely other level. The masonry is heavy but in the midst of its heaviness, because of how it has been made, that heaviness heaves and becomes animate. The transformative character of individual and collective worship is paralleled by a transformation in the material itself, a transformation which takes the material beyond itself and beyond its limits. Through the work, materials are fundamentally altered and for the first time come not into their own but into their other. In doing so they defer to other materials and other states of materiality, they suspend their self-sameness, consistency and individual objective identities in favor of being-other, being-with and being-subject to other.

Notes

[1] Martin Heidegger, Basic Questions of Philosophy. Selected “Problems” of “Logic,” translated by Richard Rojcewicz and André Schuwer. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1994: 145.

[2] Jean-Luc Nancy, Partir – Le Depart. Montrouge: Bayard, 2011: 29-30.

[3] Jean-François Lyotard, The Inhuman. Reflections on Time, translated by Geoffrey Bennington. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992: 40.

[4] See my Agencies of the Frame. Tectonic Strategies in Cinema and Architecture. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2010: 6-7.

[5] See my Agencies of the Frame: 16.

[6] See my Theorising the Project. A Thematic Approach to Architectural Design. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011: 183-4, 250-2.

[7] See my Agencies of the Frame: 305-9.

[8] Martin Heidegger, “The origin of the work of art,” in Poetry, Language, Thought. Translated by Albert Hofstadter. New York: Harper and Row, 1975: 42.

[9] Heidegger, “The origin of the work of art”: 41-43.