Darker, slower eloquence

2012

Abstract

One day, architecture’s ubiquitous drive to futural, fabulous speculation will have to face up to something lost along the way: place, poetics, myth, nature, heritage. There remains for architecture to reinvent a language, a mythopoietic, tectonic language with the capacity not only to register absence without reification or sentimentalisation, but also to take what has irremediably withdrawn from it to the verge of eloquence. This paper attempts to sketch the conditions of such a speaking (out); the framework for an architecture of resistance to the hegemony of spectacle and novelty that continue to plague the architectural imaginary, in favour of something darker and slower, taking instances from music (The Necks, Arvo Part), cinema (Andrey Tarkovski) and architecture (Sigurd Lewerentz).

Expanding

The arts are expanding—architecture expands into cinema, computational simulation and fabrication; music expands into the material and machinic vibrations of the military/industrial complex; cinema expands into AI, VR, CGI and gaming. The arts have always been tantalisingly close, to the extent that each functions as a virtual threshold for the other: poetry for music; music for architecture; architecture for cinema. Yet the arts are radically disparate. The Muses form a community, but they have nothing in common.[1]

Many are recent claims that architecture is not about building but about much more than building.[2] As if building were a minor or accidental condition of the architectural. Are such claims made by those who have no voice to think or speculate through architectural production—through architectonics and through building as such? Might they evidence political manoeuvres to substitute other kinds of voices and agencies in order to constitute parallel forms of power and control? Hence the value ascribed to where architecture `is heading,’ to innovation, to the `broad’ and the `beyond,’ to the `expanded territories’ that architects may not have ready access to. Likewise the call for relocating the discipline interdisciplinarily, transactionally, transformatively—in other words, to displace it `elsewhere.’ Where else? Into the technosciences—medical engineering and imaging, computational simulation, CGI, the immersive multimodal performance art, geomorphological, statistical, climatic, chemical or biological modelling; gastronomy, viticulture… Little is spared in this `leveraging’ of different angles on the discipline, different footholds and voices.

No doubt, in expanding something is gained—a field is amplified or taken to a higher power. It assumes greater scope, a larger set of compossibilities. It also grows in its capacity to fascinate, create desire or generate new economies: political, libidinal, material… The energy that attends this expansionist drive is undoubtedly tied to capitalist imperatives (for globalisation, exponential growth of goods, processes, markets, images…) and, in the guise of novelty and futural promise, the attendant apparatuses that produce desire (libidinal economy), manipulate retentional capacity (ADD)[3] and produce infrastructures and mechanisms of control.

But these tendencies are not necessarily inviolate. They are not `natural’ outcomes but constituted of epistemological and philosophical registers, irrespective of how foregrounded these are in our ways of being, thinking, speaking and speculating. These registers have a history. Or else, do these claims call for a genuine recasting of the architectural, and on what grounds? Two arguments come to mind:

The world has moved on, traditional disciplinary boundaries are henceforth unviable, debilitating and regressive; architecture will become irrelevant unless it regroups and finds new voice and agency.

The formal and tectonic conditions of architecture are exhausted, there is no more to say; new situations, narratives and lexicons need to be elaborated.

On that basis, a widespread devaluation of architecture’s formal, tectonic conditions immediately follows, framed by a recognisable modernist trajectory entirely directed towards evolution, progress and the future spectacular; and markedly impatient, if not dismissive toward whatever stands to delay its arrival. But are not such grounds radically conservative? Is their objective not to safeguard the profession, albeit in modified form; to not let it dissipate, to not let authority and control slip away to others? Yet, if modernity is by definition anti-conservative then it must by definition be `disservative’—that is, rather than keeping and withholding-together (con/com), it will always tend to serve-apart (de/dis). Its modus operandi is disservice. The `modern’ is what pertains to the modo, the `just-now, in a (certain) manner.’ Tied to both measure and manner, the `modern’ begs a sense generally not imputed to it: the constitutive alignment of manner, mode, mood or style and measure, matter or form—the first related to techne and ethos, the second to praxis and aesthesis. The commonplace meanings of contemporaneity and currency or `current fashion’ are relatively late (17thC). The lexicon derives from the etymons *MEN = to bind, limit and *MED = to think, consider, reflect upon. To meditate on (Latin: meditare—cf. `mediate’) and to look after, care for, heal, cure (Latin: mederi – cf. `medical’) are cognates. Both relate to the theme of the mean and the middle—essentially an ethical undertaking or medial practice of tempering and conciliating.

What else, today, could be said about the modern? Is the concept not exhausted? Yet this sense of solicitude that haunts the idea is disarming, if to be modern means to serve, attend to, keep watch over, maintain and care for. This careful medial attentiveness, this concern for the milieu, is not a passive disposition or countenance, devoid of undertaking. On the contrary, soliciting means rousing, agitating, setting in motion. Solicitation summons and cites; it is a kinematic praxis.[4] Something surges or emerges, yet without breaching any limit. The German words for care (Sorgen), concern (Besorgen) and solicitude (Fürsorge) all hinge on Sorgen, ‘surging.’ In contrast with e-mer-gence, or what comes ‘out-through-the-margin,’ surgence is a surfacing by which what arrives does not leave the surface but appears as a kind of fasciculation or scintillation that preserves the integrity of the ground. Hence solicitude does not merely attend to the release of latent potential. It safeguards potential by maintaining rather than expending it—revealing both its presence and its unfathomable reserve.

Surgence, emergence, resurgence, insurgence, expansion, evolution, broadening, exploring, innovating—the lexicon begs a line of inquiry which is foundationally a matter of limits. Beyond the oppositional logic of limits—either this side or that—might there be a way of thinking the limit outside of or aside from the `expanse,’ the `span’ or `spacing’ itself? Rather than looking beyond, consider the words themselves. The common etymon of `expanse,’ `span’ and `space’ is *SPA, which designates both the `measure of a stretch’ (Latin: pandere—an unfolded or extended interval in space or in time) and `joining’ or `fastening’ (Old English: spannen = to clasp, fasten, stretch, span). The related etymon *SPEN means to draw, stretch, spin —as if subject to weight (Latin: pendere = to hang; pondus = weight of a thing, measured by how much it stretches a chord) and to think, consider, weigh up or ponder (Latin: pensare). Evidently, thinking and thoughts weigh.[5] Curiously, another kind of measure, the metrical foot of two syllables, spondee, is named after the meter accompanying libational chants (Greek: sponde = solemn libation). Making such libations is spendein—spending as pledging, making an offering, promising engagement, performing a rite, sacrificing. Finally, this spending is by nature spontaneous; it surges of its own accord and springs out wiilingly, freely out of itself, sua sponte.

The point of this excursus? Essentially, that `expanse’ is poised on contraction; that spanning and spacing are founded on a concurrent retraction; that such retraction is the mark of a withholding tendency to join and connect accompanying every surgence. In other words, the limit is always a medial region of contesting forces and trajectories, rich with transactional potential—never a singular borderline delineating opposites. So instead of instead of expanding `beyond’ a limit into other domains to extend and overlap reach and scope, might there be a manner of testing the limit `internally,’ `retractively’ and by way of external influence—that is, not outwardly but into the resistances that both define a discipline and enable it to eclipse itself sua sponte? Might this be enabled by devising `openings’ in the disciplinary fabric itself through stressing or dilating, compacting or saturating its constitutive substance and structure, its texture, grain or nap, its mass or density?

Figure 1. Sketch of Sandro Botticelli, Cestello Annunciation (1489-90)

Consider Botticelli’s Annunciation (Figure 1), where the constraining `frame’ of the painting enjoins the psychological experience of the Virgin’s discomfiture at hearing news of her impending destiny; or again Bosch’s Triptico de Los Improperios (Figure 2), where Christ fixes His gaze on the viewer who is thereby effectively projected into the past and implicated in the causes of His predicament.[6]

Figure 2. Sketch from Hieronymus Bosch, Triptico de Los Improperios (1510-1515)

Both instances show what it is still possible to say by working and maintaining the constitutive limits of framing, portraiture and representation. At least this is my contention; and in the three instances that follow from music, cinema and architecture, I would like to suggest that in outwardly `expanding’ we risk overlooking the inner capacity of a discipline—and in particular architecture—to be, sua sponte, brought to account, to account for itself and for what is proper to it.

Festina lente: hurrying slowly

For Russian filmmaker Andrey Tarkovsky, the temporality of the cinematic shot is not determined by the chronological time of the take or the editing, but by what he calls “the pressure of the time that runs through the shots.” His aim is not to render an exact sense of chronological time but a sense of the existential character of the time proper to the affect being conveyed, by explicitly and purposefully manipulating realistic duration: stressing time, subjecting it to tension and pressure in order to dilate or intensify it into an altered time, closer to the temporality proper to the moment. The goal is not spectacle but ethos—not to create special effects but attend to and enable the special characteristics and ambiance of a given moment to emerge in a genuine way.

Tarkovsky’s time-pressure is not a vague notion, but something physically “imprinted in the frame.” It has material and substantial (rather than merely referential, metaphorical or symbolic) presence, and can therefore directly affect the film’s reception and experience. Time-pressure is both an internal state of tension within duration, and a specific tendency, dynamic or inclination that constitutes the duration’s outward trajectory and transactional potential—something Tarkovsky calls “operative pressure, or thrust.”52 The idea corresponds in music to the inherent dynamics of a tone, given the mode or scale in which it is set. Individual tones and groups of tones, runs or chords, will manifest particular energies, kinetics, tendencies and propensities or “desires”—for example the tendency to repetition, to remain in suspense, to be resolved, to lean towards chaos, and so on. Music then becomes the management and assemblage of these propensities towards a given dramatic purpose. A good example is The Necks’ performance of Aether (2001), which conveys a sense of interminable beginning and infinite finishing. The opening structure consists of four chords. The first three are repeated and harmonically open while the fourth is lower and harmonically closes the sequence. This motif is repeated with varying duration between the chords at each iteration, reducing over the length of the piece. Over and above the chords, multiple layers of sound are introduced—first wholly within the chord intervals, then overlapping and extending across chords until they develop continuity and extend across the repeating motifs. These layered sounds are piano notes, percussion beats and riffs, bells, organ and electronic sound textures whose eventual overlapping overtake the initial fourfold structure. The sound texture very slowly fills and densifies musical space, while the increasingly reducing duration between chords and beats compresses and accelerates time. The piece creates its own tempo and temporality. Because of its immersive character, and the psychosomatic affect of music, chronological succession is supplanted by a wholly other existential temporality that totally conditions its reception and experience.

Well into the piece, initially unconnected and suspended tones come to be linked into variations on a run of paired notes, unfolding into an assertive short and repeating melody that is doubled by multiple variations and echoes. In this way the music pivots on the interval between the initiation and termination of a melody that is interminably sought and endlessly deferred. This deferral is musical and temporal since it works both harmonic and durational material to create compressions and dilations, contractions and expansions, densifications and rarefactions of the tonal and temporal fabric. In deferring melody the dynamics of overlaid chords constantly point in its direction but also disperse into multiple retreats and detours without ever acceding to, declaring or setting upon it. The reiterative deferral being played out functions to preserve pure musical energy and to maintain rather than consume the melodic potential latent in the mode or scale in which the chords are set. At the same time, the piece builds in density, complexity and texture through figural overlay, instrumental timbre and rhythmic juxtaposition. The rhythmic pattern thickens to such an extent that it becomes pure and relentless beat, tending to but never reaching its limit in the single wavering and shimmering tone that opens, underlies and concludes the whole piece. What Aether performs is a process of intertwined envelopment and elaboration of possibilities, articulated from pure acoustic and resonant material through a practice entirely founded on the kinetics of sound and time.

Another example might be Arvo Pärt’s Festina Lente (1988-90), where the same melody is played simultaneously by three groups of instruments at three different time scales—slow, natural and fast. The instruments begin together but the disjunction in tempo causes the three streams to immediately diverge. During the piece, the three will develop radically different dynamic and harmonic relationships as they separate, cross-over and align with each other. This will range from resonance and concord to complete discord and chaotic deconstruction of the melody; from dynamic alignment, upgathering and amplification to an extreme opposition and cancellation of energy. Festina Lente is an investigation of music as the playing out of pure resonant time, which parallels Tarkovsky’s contention that cinema is first and foremost a tectonics of time. The contradiction in the music’s title—festina lente means “to hurry slowly”—also defines its ambit. By overlaying one melodic pattern with its accelerated and decelerated variations, Pärt constructs an image of time in the process of unravelling and decompressing—the present put into tension and stress by the antagonistic of a propellant future and a restraining past. The piece moves from stable regular organisation to irregular coagulations of multiple layers; then inexorably towards deconstitution as the texture of the piece disentangles into broad horizontal sheets of sound decreasing in proximity, separated by intervals growing in distance. Pärt effectively spatialises both sound and time through a texture that fades to an indefinite and infinitely finishing end.

Memory, collapse, recollection

Comparing the centrality of time in film and music, Tarkovsky writes of cinema as a tectonics of time:

“Of course in music too the problem of time is central. Here, however, its solution is quite different: the life force of music is materialised on the brink of its own total disappearance. But the virtue of cinema is that it appropriates time, complete with that material reality to which it is indissolubly bound… Time, printed in its factual forms and manifestations: such is the supreme idea of cinema as an art… What is the essence of a director’s work? We could define it as sculpting in time.”[7]

The factuality and materiality of time does not refer here to concrete chronological time, but to the particular time or duration—“the very movement of reality: factual, specific, within time and unique”—that attaches to events, objects and people interacting in particular situations and circumstances. Various time frames, rhythms or tempos are made to coexist within chronological time without necessarily following or being subject to it. This phenomenological, experiential and existential temporality—subjective at the core—parallels the existential spatiality that constitutes place as something exceeding concrete abstract space.[8]

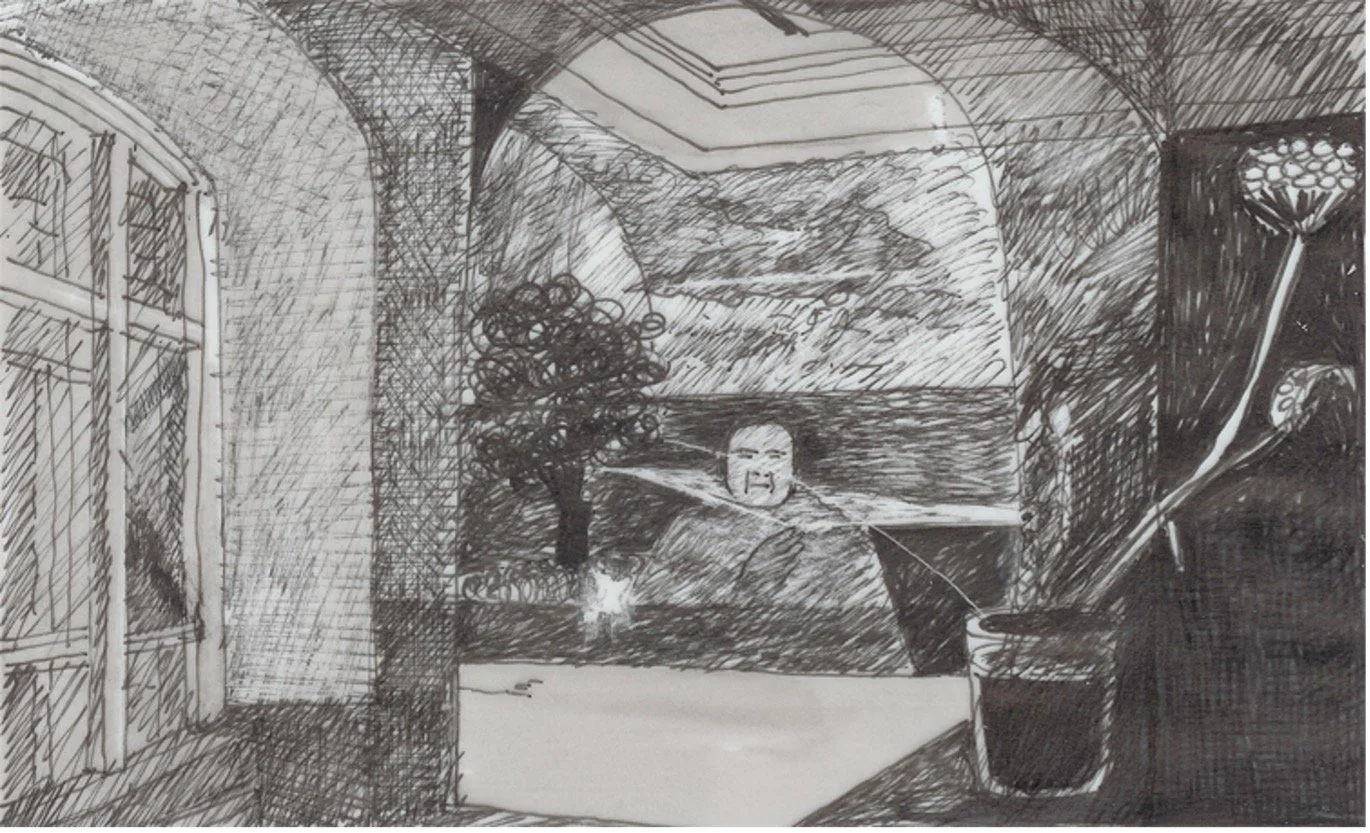

Figure 3. Sketch from Andrey Tarkovski, Mirror (1975)

In an extraordinary sequence of Mirror (Figure 3), the protagonist is shown as a child before his mother’s dressing table mirror. As he looks into it the scene shifts to the past and his young mother washing her hair. The woman is framed within a dark, glistening space with mirrors dissimulated into the deep background. Her slow, deliberate gestures slow time down and convey a premonitory tone. As she stands dripping in the centre of the space the entire room begins to weep water from all surfaces and collapse. Tarkovsky films this moment in slow motion. The young woman is then shown reflected in her mirror, surrounded by surfaces of extreme elemental materiality—water washing over glass; rough, opaque and wet masonry; walls with gnarled welts like oozing bitumen. The scene then shifts to a dark room, presumably the same room at a later time, in which, again presumably, the protagonist’s now elderly mother approaches the glass (Figure 4). The mirror doubles a window set alongside it, and is unframed so that it does not read as an opening in a wall like the window, but as pure surface and aperture.

Figure 4. Sketch from Andrey Tarkovski, Mirror (1975)

The mirror’s ambiguous position (it appears suspended in space and part of the room’s boundaries) and its transparent immateriality that yet reflects multiple overlaid images, situate it as a threshold to other worlds within the room itself. The woman raises her hand and places it on the glass. This gesture not only validates but produces the duality of the two sides and the filmic boundary that separates them. She looks into the mirror as if questioning the materiality of its surface, as if it were on the verge of yielding and giving access to the multiple spatialities and temporalities of memory. The surface of mirrors operates in several ways but always as a cipher of cinema itself. It is a filmic screen onto which images are projected—but from both directions, and exchanged into both of the spaces that front onto its surface. It is a frame which delimits and veils compossible worlds; a translucent doorway connecting places and times; an apparatus of memory, recollection and projection and a surface of monstration.

The collapse of the room marks a crisis in the concrete reality and existential milieu of the scene. The actual time of the sequence is left ambiguous since multiple temporalities are simultaneously fielded. There is clearly a looking back to the author’s childhood in the early scenes. The old mother might herself be looking back, looking forward, returning from the dead or returning to meet her younger self. The question is less a matter of conveying chronological accuracy than of showing the circulation of real and imagined, actual and virtual, remembered and projected places, times and events within a single setting made possible by this rupturing plane of inflection. The implausibility of the event amplifies this moment of crisis, enabling the images to convey more realistically what an experience of this rupture might feel like. It is not only the room that collapses but all the spatial, temporal and subjective coordinates of concrete existence. The moment triggers a disorientation in the subject and an avalanche of images which had welled up, to only now break through the resistance of forgetfulness—just as water violates the architectural skin and takes with it all guarantee of stability, shelter and safety. The sequence works metaphorically to convey, through a monstrous architectural catastrophe, the exposure of consciousness to a surfeit of the repressed memory and potentiality of the subject.

Tectonic overcoding

At the churches of St Marc and St Peter, Swedish architect Sigurd Lewerentz makes predominant use of brick in floor, wall, roof and fixed furnishings. At Björkhagen (Figure 5) the brick walls are laid in free running bond, with contrasting light grey mortar for the widely varying beds and perpends. This gives the walls the quality of pure texture and surface rather than the mechanically regular, modular quality normal for brickwork. The surfaces read like a patinated rockface, a tight fabric or gauze that billows outwards into the birch grove surrounding the building; and to such an extent that its mass, surfaces and cubic presence begin to vacillate. This achieves an unexpected leavening of materiality, a forwarding and receding of surfaces and fields so that the boundary ceases to delimit and begins to encompass.

The chapel ceiling is of shallow clustered brick vaults, set within steel I beams which span across the width of the space (Figure 6). The beams are laid in alternating converging fan shapes in plan, and in an alternating sloping pattern in section. Together, they give the ceiling the quality of a tent fabric billowing upwards. Ceiling and walls lose their interiorising, enclosing and spatially compressive character. Their limits and the density of their material presence begin to fluctuate and loosen their grip on the interior.

Figure 5. Sigurd Lewerentz, St Marc, Björkhagen, (1956-60). Figure 6. St Marc, interior ceiling.

Lewerentz’ working of masonry seems directed to a dematerialisation of mass and of the sharp edges and outlines that reinforce volumetric gravity and weight. He does not achieve this deconstitution of the building’s materiality through a literal fragmentation of forms, a substitution of non-Euclidean geometries or lightweight, transparent and translucent materials. Instead he achieves it in the material itself, using standard components, formal typologies, technologies and processes, but subjecting these to modest shifts and stresses and to modest small scale moves that carry considerable tectonic and experiential implications.

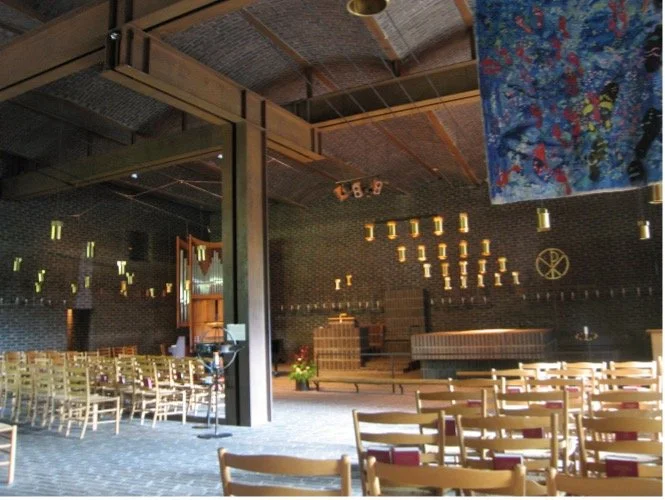

At Klippan (Figure 7), the material and tectonic moves are more risky but also more significant. The three existential and structural dimensions of space—up/down, left/right, front/back—manifest in architecture by the ceiling, wall and floor, are here fused together by a common material. Each becomes a modulation or reverberation of the other, rather than being radically distinguished as three separate and separable components of architectural space.

Figure 7. Sigurd Lewerentz, St Peter, Klippan (1962-66).

The floor reads as a woven surface of homogenous pattern with no predominant direction (Figure 8). The wall functions more like a carved mass, its thickness giving reveals, openings and the interior space itself a cave-like quality. The roof is the most liberated element in its form and its remoteness from light and the ground. The uniformity and palpable difference between the material and tectonic character of these three components allows Lewerentz to conjugate and diversify the ambiguity of the space.

Figure 8. Sigurd Lewerentz, St Peter, Klippan.

Interpreting Lewerentz’ Chapel of the Resurrection at the Woodland Cemetery, Stockholm, Colin St John Wilson notes the disengagement of the building’s portico and its slight angular shift from the main volume, as well as the chapel roof and eaves that hover above the wall cornice. He reads such modifications to or “abandonment” of classical architectural syntax as having both programmatic and symbolic functions. They create an enigmatic, ramifying and insistent strangeness:[9]

“...to what end did Lewerentz, the most poetic master of the classical language of architecture in this century, abandon that language? As a student of Schinkel, Lewerentz would have been aware of that master’s own conviction that the means of architecture would have to be ‘created anew. It would be a wretched business for architecture… if all necessary elements… had been established once and for all in antiquity’ but Lewerentz’ concern lay at a much deeper level than the pursuit of novelty…. In the Church of St Peter… an unprecedented austerity of means prevails. But this austerity is not an end in itself—it is the means by which the tragic aura of the Mass envelops us with a breathtaking primitiveness. Once again there is the element of strangeness… The building’s mystery lies in the discrepancy between its apparent straightforwardness and its actual obliqueness. The harder you look, the more enigmatic it becomes.”

To venture an explanation of how this enigmatic quality is achieved, St John Wilson cites Lewerentz’ own motto for his work: “Mellanspel”—meaning a playing (spel) between (mellan). The contention is that Lewerentz sets up various antinomical oppositional themes, which he then plays or shuttles-between to create discrepancy, ambiguity, indeterminacy and obliquity. From that result a sense of enigma and unexplainable mystery that St John Wilson implies might be proper to a sacred building. The discrepancies which Lewerentz plays out in the geometry and materiality of St Peter do confirm this.

The plan is square rather than basilican, therefore centralised rather than linear. But the altar is not literally centralised in the space. It is located just to one side of the central axis and diagonally opposite the entrance door (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Sigurd Lewerentz, St Peter, Klippan, diagram of the chapel floor plan showing multiple axes of symmetry, alignments and misalignments.

While the space is square, which in an ideal version no single direction predominates, Lewerentz carefully but forcefully differentiates between several of the axes that traverse and bisect the space. There are four entrances into the chapel. These are differently proportioned and unaligned to each other, to the room’s cross axes or to anything in the four quadrants. One entrance is into the north-west corner from the wedding chapel; another is into the south-west quadrant from outside; a third is into the south-east quadrant from the external L shaped courtyard and the last into the north-east quadrant from the sacristy. The axes linking these doors and the altar form a cross that is unaligned to the cross axis of the geometric centre of the room, or the cross axis through the central column. Such a discrepant structuring of space produces multiple gaps and misalignments that add to its resolute indeterminacy.

Lewerentz simultaneously adopts and departs from normative formal and co-locational rules of church layout. He works the space and he works into the space so as to overlay multiple overlapping geometrical alignments, directions and dynamics that contest the apparent simplicity of the square and distort its rational order. The offset position and different orientation of elements—floor paving patterns, vaulted ceiling, entry doors, windows, baptismal font, congregation, choir, altar, organ and so forth—create a web of geometric and spatial tensions that charge the space. The vaulted ceiling billows in uneven waves due to the alternating pattern of ribs (Figure 10). The undulating, folded brick ceiling is read against a pair of deep steel beams that give mid-span support to the vaults and span the full width of the space. These beams sit on a secondary beam, almost imperceptibly asymmetrical to the single column that supports it. The column is marginally off centre within a space that is exactly square. The column and beams are themselves assembled from two unequal sections with gaps between them sufficient to allow light through their mass. The asymmetry of the column is reinforced by the offset assembly of beams—the two major cross beams also having the effect of countering the orientation of the vaults. This steel assembly effectively subdivides the square chapel into four smaller regions. The altar is marginally offset to the south of the central axis of the room and placed in the quadrant opposite the entry door. The baptismal font is in the quadrant closest to the entry. The lectern and organ occupy the third quadrant and the major portion of the congregation occupies the fourth. None of the windows or doors is symmetrical to or aligned with the geometric axes of the whole space, or with the quadrants in which they are located. The combined effect of this highly complex but barely perceptible setup, made of very slight nuanced geometrical shifts and overlays, is considerable.

Figure 10. Sigurd Lewerentz, St Peter, Klippan, vaulted brick ceiling and composite steel beam

In terms of directionality and dynamics, the ceiling vaults run west-east towards the altar to emphasize a processional direction. This conforms to a traditional liturgical orientation. At the same time, the vaults rise from each side to a north-south pitching ridge above the column assembly. The combined effect is to stretch the west-east dimension and at the same time to gather, centralise and raise the space upward. This tension between two tendencies holds the space in suspense, in an indiscernible state somewhere between stability and dissolution. In the brick floor the bed joints run north-south, but at an angle to the square plan.

Figure 11. Sigurd Lewerentz, St Peter, Klippan, sketch of multiple brick paving directions in the chapel. North is uppermost

Within this linear pattern Lewerentz inserts several areas of paving at other angles—like rugs or patches set within a larger web (Figure 11). Only the paving in the zone of the altar conforms to the orientation of the walls. Despite reading more like a woven multidirectional surface than a linear array, the heterogenous patterning of the floor counters the orthogonal alignment of the overall space and the altar, as well as the walls. These contrasting shifts in pattern and geometry create disjunctions and incommensurabilities in the spatial order and slow down or discharge the dynamics that suffuse the room.

The intricate juxtaposition of geometries, spatial directions, tensions and proportions tends to overburden, materialise and condense the space; turning it from an empty container into a solid woven network. At the same time, Lewerentz mobilises the materiality of the space, causing it to fluctuate, alternate and oscillate—but in minor, almost imperceptible ways. This imperceptibility, made more acute by the dimness of the interior, conveys Lewerentz belief that “the nature of the space has to be reached for, emerging only in response to exploration.”[10] St John Wilson has read this as a desire of Lewerentz’ to convey and represent the numinous. But the tectonic implications exceed any semantic, metaphorical or symbolic readings that could be ventured for the building. What Lewerentz achieves spatially, tectonically and materially has important value in terms of transferable strategic agency. The central armature that supports the roof may well evoke the cross on Calvary, but it also has a significant role in zoning the space to foreground the differentiated collectivity that characterises a congregation. It works to gather and amplify a distinctive weightiness in the space—a gravity that corresponds to the internalised disposition of grief and joy that surround reflection, prayer and celebration in the Christian mass. It acts as a pivot that keeps the various sectors and trajectories of movement in asymmetrical balance as if to convey a sense of anticipation and suspense, or to frame the conditions of advent and of the uncanny. As such, the armature enables and mobilises before it represents. It turns an abstract spatial structure into a world or a place, calibrated to specific modes of being, of being-with-others, and of being-with-otherness. Lewerentz does not achieve this through formal complexity, large-scale compositional moves, distinctive articulations and separations between parts or unusual geometries. The scale of his tectonic endeavour is extremely modest, but every move carries considerable weight and enduring affect. He does not abandon architecture’s foundational tectonic dimensions or remit but works at the tectonic by subjecting it to significant strain and working it until it yields.

Darker, slower eloquence

In each of the instances I have cited, speculation and innovation emerge in the materiality of the respective works, in their structure, grain and substance; by holding to and working what is proper to their respective disciplinary field—music, cinema, architectonics. None of them promotes an `expanded’ territory that would overreach into other neighbourhoods. Each work produces insight and innovation by manipulating the normative conditions and boundaries of its own domain (sound for music, the moving image for film and tectonics for architecture). In that sense the works are radically conservative because they remain with the radix or roots and foundational constitution of their discipline. The perspective ventured here is likewise conservative since it promotes the sustainment of a dynamic and risky process that pivoting on the radical, rather than maintaining a static state or familiar, safe outline.

The recurrent tactic involves putting the material conditions of a particular discipline under strain and duress—subjecting them to considerable stress until those conditions massify and coagulate or dilate and yield. In both cases, something novel emerges, something dark and eloquent. It does not arrive by overlooking or eclipsing structural or material limits, but precisely by iteratively (re)working those limits; leavening or spatialising the borderlines until they produce an interstice, interval or residual region: that is, a novel circumstance that remains to be transactionally (net)worked.

Notes

[1] See Jean-Luc Nancy, `Why are there several arts and not just one (Conversation on the plurality of worlds),’ in The Muses, translated by Peggy Kamuff (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996), 1-39. Nancy’s argument develops from the (philosophically and historically) situated notion of `art’ as a singularity; whereas the arts, each related to a distinct sense, constitute an irreconcilable yet consilient multiplicity.

[2] For example, as promoted in Formations for the Australian contribution to the Venice Biennale by Anthony Burke, Gerard Reinmuth with TOKO Concept Designs: “Describing the exhibition, Gerard said: "By exploring innovative practice types and their design output, the exhibition will provoke discussion around issues of the future of the profession and the kind of problems architects are becoming involved with." Outlining the exhibition focus, Anthony said: "It's very exciting to see where architectural work is heading, the new domain areas that are being explored and the vitality and variety of innovative architectural types that Australia seems to foster." They added: "'Formations' tackles questions such as: What are the influences shaping the built environment and how are architects creatively responding? How are architects thinking more broadly about their role and having a positive influence on the built environment? Is it possible to think of the architect as just 'one thing' any more?' See http://www.architecture.com.au/i-cms?page=1.64.34.15164.17622 (accessed 7 March 2012).

[3] Bernard Stiegler has made a connection between technology and memory through the motif of mnemotecnics—that is, the intrinsic ‘retentional’ role of technology in embedding knowledges and practices in the objects, systems and apparatuses (dispositifs) that it produces (language, ritual, books, tools, music, buildings, films). See his Économie de l’Hypermatériel et Psychopouvoir (Paris: Mille et une Nuits, 2008) and also Giorgio Agamben, “What is an Apparatus?” and Other Essays, translated by David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009).

[4] Greek: kinomai = I go, I hasten. Cf. kinesis, kinesthesis, `cite’ and `cinema,’ from the same etymon. That to `cite’ means to summons (and not merely to `reference’) is intriguing, but likely anathema to modernity’s abiding Protestantism.

[5] See Jean-Luc Nancy, The Gravity of Thought, translated by François Raffoul and Gregory Recco (New Jersey: Humanities Press, 1997).

[6] I gloss these two works in Michael Tawa, Theorising the Project. A Thematic Approach to Architectural Design (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011), 157-159 and Agencies of the Frame. Tectonic Strategies in Cinema and Architecture (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2010), 142-144, respectively.

[7] Andrey Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time, translated by Kitty Hunter-Blair (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006), 94.

[8] Jeff Malpas, Heidegger’s Topology. Being, Place, World. London: MIT Press, 2008), 92-96.

[9] Colin St John Wilson, `Sigurd Lewerentz. The Sacred Buildings and the Sacred Sites,’ in Nicola Flora, Paola Giardiello and Gennaro Postiglione (eds.), Sigurd Lewerentz 1885-1975 (Milan: Electa, 2001) 21.

[10] St John Wilson, `Sigurd Lewerentz,’ 20.