Atmosphere of the sacred: the awry in music, cinema, architecture.

Discomfiture

There is a troubling condition at the core of Christian theology: Christ leaves and leaves us be – forsaken, abandoned to oblivion and exposed to the withdrawal of God. And yet, hope against hope, in the words of the Apostles’ Creed, we ‘look to the resurrection of the flesh (carnis resurrectionem) and the life everlasting (vitam aeternam)’.1 Hope is all we are left with, and that hope is invested as a sustained theological tradition of light and transcendence, translated architecturally, at least since the Gothic, through luminosity, levity and dematerialization of the built fabric of the church. A theology of obscurity is admitted, and finds its architectural expression in the gloom, or better, in the gloaming spaces of shadow, dim reflection and obscurity. There is a via negativa, an apophatic theology – a theology of deferral, circumspection and silence – that counters the via positiva of kataphatic or affirmative theology of speech, and that is commonly associated with mysticism. But Christianity predominantly develops the sacred through a theology of light and affirmation that marginalizes obscurity, uncertainty and doubt.

What is ‘the sacred’, though? Generally, it only exists in oppositional terms, over against a counterpart – the profane or the secular – to which it remains distantiated and irreconciled. In some respects, this oppositional construal serves to maintain the privilege, authority and power of the first over the second; or else the sacred is unacknowledged, as it is in modern architecture where a resolute secularization (or aestheticization) of conditions historically associated with the sacred are displaced into the phenomenological, haptic or experiential. In all this, normative oppositional thinking has left unexplored the constitutive identity between sacred and secular.

Fundamentally, both are a matter of sequestration. A clue is in the etymological root *SEG, to cut (one region/territory from another). Hence, sacred and secular have to do with the borderline, the limit, and, at the same time, with measure, with segmentation. Likewise, the temple (Latin templum, Greek temenos) – that is, sacred space as such – is a place reserved and withdrawn by being cut off from the everyday, from existential temporality and spatiality. ‘Temple’ is from the etymon *TEM and Greek temnein, to cut, in the sense of being cordoned-off and ‘held’ (Latin tenere) by a stretched string (ten-) that demarcates a boundary. This demarcation produces sacred and secular in the one gesture of sequestration.

Following Giorgio Agamben and Jacques Derrida, between sacralization and profanation there is only the most infinitesimal shade of sense – a shift of register maybe, or of scale, power, tint or nuance.2

Figure 14.1 Gloaming space of shadow, dim reflection and obscurity. (War Memorial, Canberra).

Photograph by Michael Tawa, 2015.

Figure 14.2 Uncanny circum- ambience. (Anish Kapoor, Cloud Gate, Chicago, 2006).

Photograph by Michael Tawa, 2014.

So it is that humanity creates the two terms, and the opposition between them, in order to then either join or separate, reconcile or estrange them at will. The two regions or conditions are initiated by the same gesture of sequestration that separates and removes, safeguards and abandons, secures and consigns to oblivion.3 Unsurprising, then, that the rational, secular project at the heart of modernity remains interminably haunted by the spectre of the sacred and incessantly looks for means of sanctification – for example in proportioning systems that intimate transcendent order; in pervasive narratives of peregrination and journeying towards light; and in alchemical references to base and transcendent, ignoble and noble materialities.

The troubling condition I began with – the simultaneous presence and absence of Emmanuel (God with us) – is not therefore antinomical, dichotomous or complementary. It is not black and white, nor either-or. Rather, it is both-in-both, in the sense that the gloaming of twilight is characterized by a mutual presence and transactional exchange of darkness and light, gloom and gleam. Likewise, the moment between in and out breathing, the slack sea between high and low tide or the point of contra flexure in a structural system – when one condition gives way to its counterpart, or lets its other, its ulterior or alterity, be.

This genuinely spiritual Christian experience – that the faithful is irreconcilably both forsaken and redeemed, in a state of both doubt and certainty – might well owe something to the traces of Greek philosophy and tragedy in Christian theology; but effectively, it means that the Christian confronts an irremediable condition characterized by longing – that is, by love and desire for union. The love might be unrequited (the relationship between humanity and divinity is evidently not symmetrical or reciprocal), but faith sustains it. Neither light nor dark, absent nor present, forgotten nor remembered, the faithful inhabits an interstitial, ambiguous region suspended between obscurity and clarity, knowing and unknowing, doubt and certainty, fullness and emptiness, poverty and abundance, fructification and barrenness, and so on. Neither one nor the other, and at the same time both: heard and ignored, admitted and excluded, saved and condemned. This is the particular spiritual tenor, mood or ambiance that Christianity brings to the sacred experience.

My aim here is to venture an architectural equivalent of this tenor – that is, to ask what might be the spatial and material conditions that produce such an ambiance and that in turn make it possible for the human being to become aware of and to have a lived and embodied, haptic experience of this theological (or intellectual) and religious (or emotional) moment. The distinguishing quality of this moment – the primary characteristic of the uncanny region that environs the Christian experience – has a spatial correlate, a marked circumambience in which two or more radically different, irreconcilable conditions produce between them a palpable sense of indeterminacy. The ambiance is uncanny since familiar and alien, comforting and discomfiting at the same time. And it is awry in that the normative conditions of experience are in it distorted and rendered unfamiliar.

Awry

In John Tavener’s Nativity of the Mother of God, from the 1988 composition for cello and orchestra The Protecting Veil, there is a pivotal moment when the music goes awry.4 The sustained melody of the first movement is interrupted, in the second, by glissando figures that slide from consonant to discordant tuning, introducing a strange and uncanny element. This thaumaturgical intervention – this wonder-work that alienates and discomfits the familiar – accompanies a significant threshold in the narrative: the birth of Mary. A structural alteration from consonance to dissonance, from consistency to distention within the musical fabric, signals a structural change in the fabric of the world: a patent intervention of heaven into the affairs of the earth, of the sacred in the normative conditions of human being. A kind of extensive porosity between worlds opens and unsettles things.

Yet the shift from one to the other is not bordered by any schism. Nor do the two conditions inhabit distinct temporalities or timeframes – one is not before or after the other. That is to say, the awry is present from the very beginning, as an unexercised potential that is systematically augmented and eventually overtakes the opening figures.

Figure 14.3 Things go awry. (Lighthouse, Trial Bay).

Photograph by Michael Tawa, 2015.

Figure 14.4 Extensive porosity. (Mirror, Venice).

Photograph by Michael Tawa, 2016.

In other words, the awry is not a condition that befalls, arrives from outside or develops in time. Rather, the awry is always already there.

Being sensitive to the awry – to the uncanny undertow that distorts and disorients – is also being open to the possibility of awe. Now awe is not an isolated experience but always shadowed by its foundational counterpart – terror or dread. For Martin Heidegger, ‘close by essential (ontological) anxiety, in the terror of the abyss, there dwells awe. Awe clears and embraces that place of being essentially human within which one abides at home in the abiding.’5 Awe (Scheu) is a fundamentally uncanny (unheimlich) ambiance, since in it is produced the precarious, indeterminate and irresolvable double mood (Stimmung) of simultaneous angst and curiosity – in the words of Rudolf Otto, a mysterium tremendum et fascinans, that remain in permanent suspension.6 This undecidability between terror and awe gives wonder its uncanny register.

In Taverner’s Nativity, the intrusion of another register into the circumstantial world is marked by intervening musical figures – glissando and zigzag themes that tend towards but do not touch the keynotes; sharps and flats over against the anticipated harmony given at the outset; all typical of Romani music, the music of Gypsies, Hindus, Arabs and Jews for example, or the Rembetika music of depression-era Greece. These discords produce distance, suspension and irreconcilability within the musical fabric. They also produce a sense of longing and lamentation, accompanying a sustained melancholia – usually for a lost time or place, either Heimat or Himmel, Homeland or Heaven.

Here, then, sacred and profane do not constitute an opposition, a dichotomy or complementarity, but a constitutive alteration of one in the other that marks their intimate selfsameness: a change of register or state; a dilation or intensification; an augmentation or dissimulation. In our encounter with the discrepant, awry and uncanny, something happens, something takes place – logically, structurally and materially – to render the one alien to itself.

Such alienation derives from an inherent discrepancy that creates distance and dilation between different parts, dimensions, phases or powers within an entity – a piece of music, a film, a narrative, a building.

Figure 14.5 Indeterminate borderlines. (James Turrell, Within without, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2010). Photograph by Michael Tawa, 2015.

244

Figure 14.6 Alien or deviant presence. (Bút Tháp Temple, Vietnam, thirteenth century). Photograph by Michael Tawa, 2015.

The discrepancy disestablishes the being, taking its various registers into a state of suspension and undecidability. Because these become ambiguous, they begin first to waver, and then begin to interact and conjugate so as to produce new assemblages that gather temporarily before dispersing and reassembling differently and interminably. Each assemblage has its own palpable ambiance and mood, but also integrity and logic – that is, its own consilience. In the circumambience proper to atmosphere, affects or systems coexist simultaneously, but without coincidence or alignment. The discrepancy between them produces porosity, slippage or dissonance within a texture that remains strangely consilient and consistent.

Undecidable

The final sequence in Paolo and Vittorio Taviani’s film Kaos (1984) recounts the narrator’s conversation with (the ghost of) his mother, in which she recounts an event in her youth. Fleeing Sicily by boat the family stops at the island of Lipari to rest. On the beach the children head for the high pumice cliffs that back the sea. She is older and has to remain with her ailing mother. Seeing her sadness, the mother eventually signals for her to join her siblings. They climb to the top of the blinding white cliffs and, filmed by a rear shot taken diagonally down to the azure sea that excludes the horizon line, they slowly sidestep and dance down the pumice slopes, eventually merging with the ocean. The soundtrack to this extraordinary scene is Barbarina’s aria L’Ho perduto, me meschina from Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro.

What is the aura, the ambiance of this scene? How is it produced? The atmosphere of the sequence results from several discrete but coincident conditions inherent within the cinematic set-up. First, the narrator, the author Luigi Pirandello whose short stories the film is based on, visits his empty family home after his mother has passed away. He remembers a story that his mother used to tell him when he was young. He is in a reverie of recollection, tracing evanescent memories, making sense of who he is.

The film then shifts to that earlier time and the narrative voice becomes the mother’s. There are several overlapping stories and voices – the narrator’s journey into the past, Pirandello’s stories, the narrator’s mother in her penultimate years, the same woman as a young girl at the pumice beach.

And then there is the Mozart aria. L’Ho perduto, me meschina means ‘Woe is me, I have lost it’.7 The libretto refers to a brooch that the peasant girl Barbarina was to give to the countess’ maid but which she has lost. A trifling moment in the scheme of things, sung by a minor character, but which Mozart scores to produce extraordinary emotional intensity. How is this achieved?8

The affective quality of the music could be ascribed to its being set in the minor mode (F minor). The key of F minor has four flats, and flat keys were often associated with grief and dejection in the vocabulary of the time. The presence of diminished seventh chords and three-note figures produces sharp dissonances, also associated with grief and sadness, while the use of chromatic chords (which include notes extraneous to the mode or key of the piece, hence producing an ‘alien’ or ‘deviant’ presence) adds harmonic complexity or ‘colour’.

The vocal line is fragmented, with short sighing gestures set against the persistent quaver figures of the accompaniment that together convey a sense of bewilderment and powerlessness. Contributing to the quality of unfulfilled and perhaps unfulfillable desire is the dissonance at the first ‘me-SCHI-na’: the resolution at ‘na’ being only partial and the resulting chord being unstable according to the norms of tonality. In fact, the piece never comes properly to an end because of Figaro’s interruption.

At one level, there is a disparity between Barbarina’s trifling distress and the deep scale of sadness in the music. At another, the dissonant (or internally disparate) modality of the music accentuates the emotional tension in the filmic narrative, contributing a great deal to its Stimmung. This modal disparity is at odds with the sublimely enveloping imaging of the landscape and the eventual absorption of the children's joyful abandon into the azure field.

In the film’s exquisite conjunction of narrative, image and sound, these disparities parallel the narrator’s desire to recollect his past, his desire for the mother and her youth, the mother’s desire to relive and retell the story, the child’s desire to join her siblings, the desire of the children’s falling and mergence with the sea, and an overarching and tragic desire for surrender and release. These multiple simultaneous layers produce a disseveral texture that reverberates but never totalizes into a single reading. Rather, they produce a narrative ambiance of insinuation and allusion indefinitely open to interpretation and consequently always novel and surprising.

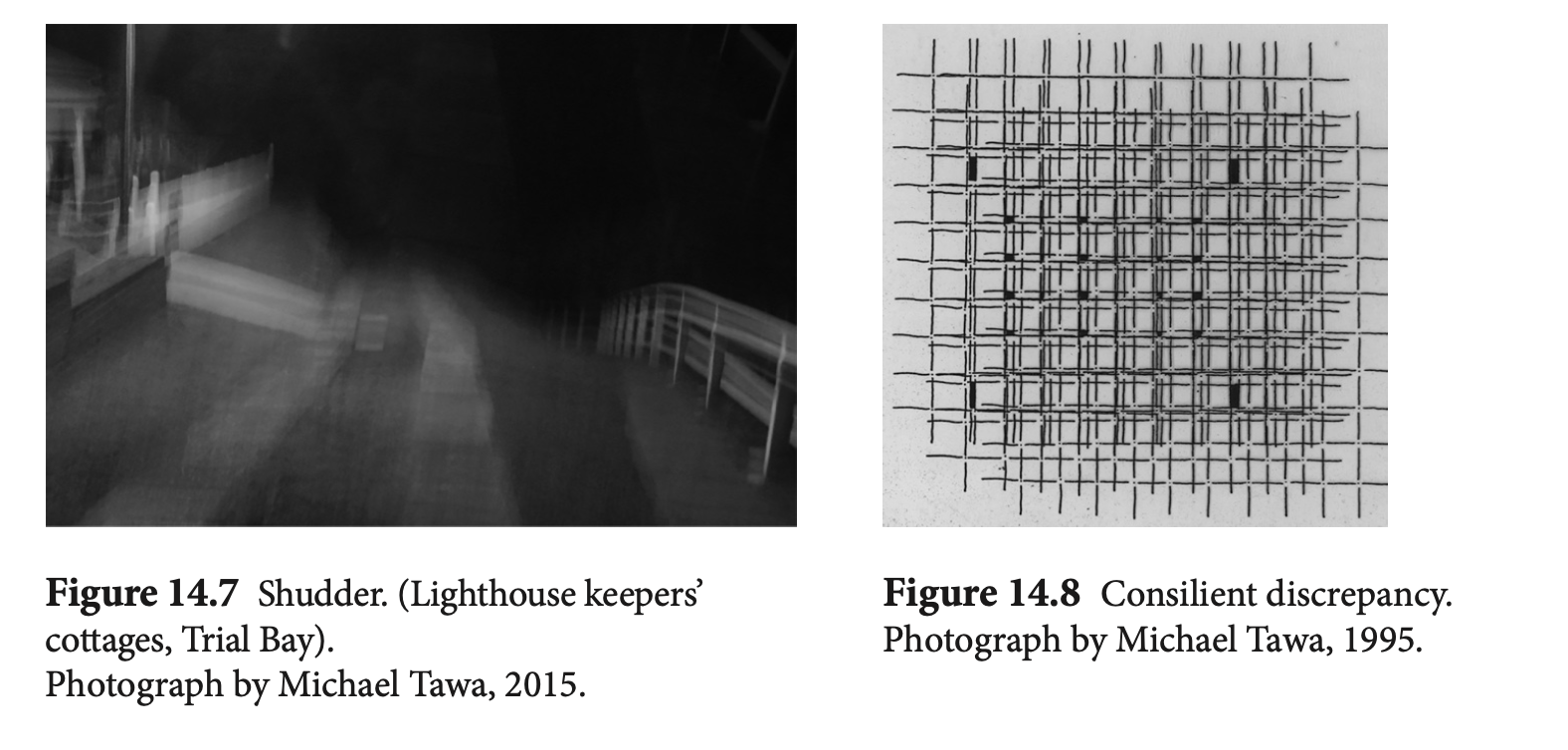

Shudder

Before turning to architecture, and to the spatial, material and haptic correlates of atmosphere in theology, music and cinema, there are four motifs that I would like to retain from the foregoing. First, atmosphere is produced by a state of consilent discrepancy. Second, consilient discrepancy results from the simultaneous coexistence of several parallel, independent parts – spatialities, temporalities, degrees or conditions – which maintain their separateness in a state of suspension, while also potentially gathering into emergent wholes. Third, the experience of consilient discrepancy is itself ambiguous and wavering. It is characterized by a sense of the uncanny, the disturbing and the discomfiting and, at the same time, of the familiar, the reassuring and the comforting. Fourth, this experience parallels a theological figure that is foundational for Christianity and for a particular experience of the sacred: an absent presence that disturbs the normative coordinates of the everyday world and intimates something of the otherworldly inherent to it.

In fact, atmosphere is properly a species of mood or temporality, rather than a physical environment or spatiality – although it does pivot on a kind of temporalization or mobilization of the spatial. We are all familiar with atmosphere as the anticipation of a moment to come, the circumambience that frames an event yet to unfold, or a virtuality yet to be actualized – a game of sport, a concert, a marriage. Atmosphere is this open (and, critically, this shared) attentiveness to what might come to pass, what might at any moment take place. It is a collective witnessing of being-in-the-moment and anticipation that is not passive but has effective agency in the sense that a collective can mobilize the latent – that is, it can activate the multiple suspended registers, promote their assemblage and unclench their eventuation.

The undecidability in the texture of consilient discrepancy is manifest and experienced as a kind of shuddering or shaking, since the indeterminate cannot rest on one or another of its factors and must interminably shuttle between them. We see this in the films of David Lynch for example, where parallel registers coincident in the one world open to each other, and in Alfred Hitchcock’s films, too, where the two worlds of reality and dream – the oneiric that is more real than the real – become indeterminate. We also saw this in the musical texture of Tavener’s Protecting Veil and in the overlaid visual and acoustic registers in the film. But what might be the architectural counterpart of these discrepant textures, of this shuddering?

The characteristic of atmosphere, founded on unaligned yet coherent multivalency, can be instantiated in architecture, which like music and cinema, has the capacity to set up productive conditions based on incommensurable, discrepant assemblages. This is possible across several registers. One is the underlying spatial or geometric system that directs relative arrangement, scale, proportion, symmetry, rhythm, patterns and shape. Another is the material and tectonic system of connections and joints that regulate the formal, volumetric and technical assemblage of parts. A further register relates to the spatial sequences, narratives and experiences enabled through the spatial and tectonic set-up. There is also a semantic register through which architecture engages allegorical, metaphorical or symbolic referents, thus relating built form, spatiality and temporality to broader conditions and currents of human knowledge and experience – metaphysical, philosophical, religious, ethical, political, social, scientific and aesthetic among others.

The degree to which these different registers are aligned, coordinated and resolved within a single work contributes substantially to its character and complexion. Where different registers and references are mobilized to circulate and wander (to wend or wind their way through the fabric of a building), they will gather, disperse and condense into semantic ambiances that give the architectural setting a distinctive atmosphere. This then triggers an ongoing process of curiosity, inquiry and discovery that seeks to understand and relate them to each other, to see how they connect and fit together across the gaps and discontinuities established between them. Consequently, a work will always produce unexpected resonances, open up new readings and generate new patterns of meaning.

In what follows I would like to explore instances of consilient discrepancy that build into an atmosphere of the sacred by analysing Sigurd Lewerentz’s Church of St Peter at Klippan, Sweden (consecrated 1966), in terms of the four registers mentioned earlier – geometry, materiality, narrative and allegory – respectively through the overlay of several discrepant alignments, axialities, orientations and disposition of component elements; through the masonry fabric of the building that shuttles between gravity and levitation; through a spatial narrative that is inherently destabilized; and through the concatenation of different allegorical and symbolic references to Christian theology.9

At St Peter, consilient discrepancy is evident within each of these four registers as well as between them. For example, there are several unaligned geometric systems within the spatial set-up, as there are discrepancies between the geometric system, the material conditions, the spatial narrative and the allegorical references. These incommensurabilities within the total architectonic montage construct a complex and dense assemblage that is open to multiple readings and interpretations. These are set within the circumambience of a very particular Protestant tenor of collective worship and individual religious experience, influenced by the aesthetics of the romantic and the sublime – but also, following Raymond Williams’ reading, according to a distinctive ‘Modern’ sensibility, emergent in the late nineteenth century and equally engaging romantic motifs: ‘the general apprehension of mystery and of extreme and precarious forms of consciousness; the intensity of a paradoxical self-realisation in isolation’;10 as well as a concern for the problematics of language, authorship and representation; discontinuous narrative; strangeness, estrangement and mystery; disconnection and unsettlement, alienation and loss.

In his reading of Lewerentz’s late work, particularly in the geometrical disposition of St Peter, Peter Blundell Jones discerns a deliberative departure from strict classicism:

“From the beginning of his career, he was interested in irregularity and conflicting orders rather that in the calm finality sought by Mies . . . and if, like Mies, Lewerentz still held to a concern for geometry and proportion visible in the completely orthogonal plan with its square within a square and carefully modulated dimensions, the three-dimensional composition of St Peter’s is untidy, asymmetrical, contextual, contingent; its irregularities are not repressed but relished. Despite the Classical rigor of an early masterpiece like his Chapel of the Resurrection of 1926, Lewerentz seems in his late work to have returned increasingly to the National Romanticism of his youth, reworking it in an entirely new form.” 11

Colin St John Wilson likewise notes Lewerentz’s ambiguous tectonics, utilizing discrepancy and obliquity, as an ‘abandonment’ of classical architectural syntax – though he sees it as having both programmatic and symbolic functions, the latter producing an enigmatic, insistent strangeness that engages metaphysical and religious dimensions of the sacred:

“In the Church of St Peter . . . an unprecedented austerity of means prevails. But this austerity is not an end in itself – it is the means by which the tragic aura of the Mass envelops us with a breathtaking primitiveness. Once again there is the element of strangeness . . . The building’s mystery lies in the discrepancy between its apparent straightforwardness and its actual obliqueness. The harder you look, the more enigmatic it becomes.”12

The plan of the main chapel at St Peter is square and thus centralized, not linear. In a square space, no single direction predominates. But here Lewerentz introduces several axial systems across the space. The altar is asymmetrically positioned against one of the walls rather than in the middle of the space, and the centre is inaccessible since taken up by a large steel column assembly. Located opposite the main west entry door, the altar also sets up a shallow axiality responding to the processional tradition of church architecture. Consequently, the room is simultaneously centralized and axial, focused and lengthened, stable and unstable, symmetrical and asymmetrical.

At least four systems are overlaid in the main chapel space, each with its own discrete implied centre and axes – in Figure 14.10, the square plan described by the four walls with its geometrical centre (Cr); the four doors that lead into the space (D1–D4); the central column (Cl) and the altar (A). None of these systems coincide. The four entrances are differently sized and do not line up across the space. They do not accord with the room’s geometrical cross axes (A1) or relate to anything in the four quadrants of the space. Each door is associated with a different function. The entry axis through the western door (A4) – the chapel’s civic address and the largest of the four – follows the layout of traditional churches. The northwest entry from the wedding chapel (D2) adjoins the baptismal font (B). The northeast entry (D3) between organ (O) and choir (Ch) is for the clergy and is positioned not quite opposite its counterpart, the southeast entry (D4), which is smaller, close to the altar and reserved for the church community. The axis (X1) linking the centre of the western entry door (D1) and the altar (A) aligns neither with the entry axis central on the door and normal to the square space (A4), the geometric cross axis of the space (A1), the cross axis passing through the central column (A2), the cross axes through the organ (X2) and baptismal font (X3) nor with the centre of the room (Cr). These multiple geometric alignments, some shifted imperceptibly in relation to others, produce a complex zoning of the space and an elusive, subtle discrepancy within what otherwise appears to be a self-consistent formal programme.

Lewerentz builds further ambiguity between the apparently commensurable, stable square plan of the chapel and a number of infinitesimal variations and misalignments that contest and destabilize it. The central column – marginally central in a space that is not quite square – supports a pair of steel beams positioned asymmetrically above it, delivering greater openness and thus greater communitarian emphasis to the western half of the room.

Figure 14.9 Sigurd Lewerentz, St Peter, Klippan (1962–6), interior view from the western entry door towards the altar.

Photograph by John Gamble, 2008.

Figure 14.10 Axial discrepancies in the plan of Sigurd Lewerentz’s St Peter, Klippan. Drawing by Michael Tawa, 2018.

This tactic creates a virtual separation and distention between the congregation and the altar, while at the same time unifying priest and worshipper, divinity and humanity in the centralized space. The apparatus that achieves these complex and ambiguous relationships – the monumental column and beams that metaphorically read as the cross of Christ: the implement of suffering and redemption, sin and salvation – functions as a mechanism that simultaneously connects and separates, enables and disables. The offsetting of geometric systems and patterns between walls and column, column and beams, beams and vaulted ceiling, entry doors, windows, congregation and priest, choir, altar and organ effectively build up a web of tensions that equally burden and relieve the space.

The spatial narrative prompted at St Peter flows from its particular geometric and material tectonics. Imperceptibly unaligned spatial systems convey a sense that everything is not as it seems, that the stable is haunted by a palpable disestablishment. The familiarity of the set-up – centralized space, altar, processional sequence, accessibility, organ, baptismal font, pews – is paralleled by a discomfiting unfamiliarity. The known takes on an uncanny attunement. In this way, architecture engages with the strange and enigmatic qualities we identified in Kaos and The Protecting Veil. These have aesthetic dimensions, but here they work to imbue the space with otherworldliness: a sense that the divine is incident yet unseen; that a transformative, spiritualizing presence is immanent, eminent and imminent.

Such a narrative resonates with allegorical aspects of liturgy and worship. The tectonic and kinaesthetic experience of the chapel’s architecture infers and indicates symbolic referends. The allegorical – literally what is ‘spoken otherwise’, saying one thing in place of another – is not duplicitous or disingenuous, however. Rather, it is in respect of the nature of things, so as not to violate them, cognisant that some can only be said otherwise, differently, indirectly, by deferral and detour.

Figure 14.11 Lewerentz, St Peter, Klippan, interior view from the baptistery towards the southeast entry door.

Photograph by John Gamble, 2008.

Figure 14.12 Lewerentz, St Peter, Klippan, brick-vaulted ceiling.

Photograph by John Gamble, 2008.

Several experiential qualities – characterized by non-oppositional and non- contradictory conditions – prompt such a reading. The space is centralized and axial. Consequently, the liturgical emphasis is indeterminately both communitarian and hierarchical – the celebrant is at once among the community of worshipers who surround the performance of the sacrament, in their midst, and before them, in Christ’s stead; God is immanent and transcendent; salvation is a gift (vertically, down from ‘above’), the outcome of faith (‘up’ from ‘below’) and of good works (towards others, horizontally).

The geometry of the space is orthogonal, apparently equal-sided and symmetrical. Yet it is also riddled with inequalities, made up of distinct systems that don’t quite align and whose infinitesimal discrepancies and deferred reconciliations quietly animate the space by rendering its apparent quadrate fixity indeterminate and disestablishing its material density: the burden of existence is leavened by grace.13

In material and tectonic terms, the gravity of the heavy masonry building lends the interior spaces a particular enigmatic luminosity or gloaming that shifts emphasis from the bright light of day to the twilights, when night and day become indeterminate, where the delineating boundaries of things become ambiguous, and in whose dusk actuality is reabsorbed into potentiality: ‘God is light’14 and ‘dwells in thick darkness’.15

Now the liturgical elements that properly furnish an atmosphere of the sacred – the temporality of ceremonial substances (pervasive incense, density of fragrance, condensation, recitation, music, reverberation, descant); the iridescence of sacramental objects (gold, silver, metal thread jacquards); the scintillation of surfaces (gold- leaf, stained glass, icons, glazed tiles) – are enabled, in combination, to produce two radically different but simultaneous and heady affects: materialization of the immaterial circumambience of space and dematerialization or vaporization of architecture.

There is the chapel’s resolute interiority and radical sequestration from the outside. The space reads as a lithic clearing, a hollow or cavern carved out of masonry. Since the floor, walls and ceiling are made of the one material, the common distinction between ground, midspace and sky, or between earth, world and heaven is dissolved. At the same time, window openings are detailed in such a way that the boundaries of the room are turned inside-out and the interior is exteriorized so that it reads as a delimited portion of the outside.

Figure 14.13 Lewerentz, St Peter, Klippan, brick floor and baptistery.

Photograph by John Gamble, 2008.

Figure 14.14 Lewerentz, St Peter, Klippan, baptistery.

Photograph by John Gamble, 2008.

The light they admit is not the calculated light of analysis and discrimination that determines the lineaments and edges of form. Rather, light gleams and glows, scintillates and, as it increases or decreases due to ambient conditions outside, brings a tidal fluctuation to the perceived scale of the space that consequently appears to expand or contract, to have its dimensions relativized, rendered indefinite and thoroughly obfuscated. A world apart, the room now hovers in an intermediate region, uncoupled from the coordinates, dimensions, conditions and laws of normative existence. Consequently, the force of gravity is eased and the weight of the architecture leavened. Again, there is a simultaneous coexistence of apparent contraries: heft and levity, mass and porosity, immobility and vitality.

Then there is the extraordinary undulating ground plane that wells up as an emergent telluric undertow, reminiscent of Michelangelo’s Capitoline Hill in Rome, which references the Umbilicus Caput Mundi or Omphalos of Delphi – the navel of the world: a weal or welt signifying the source or origin of creation and a gateway enabling Heaven, Earth and Underworld to communicate.16 This nexus brings together two symbolic figures: solidity and liquidity – concavity, hollowness and porosity making possible the flow of water as a spring or font. Mass is disestablished, dematerialized and liquefied; the immobile is mobilized; substance is transmuted and essentialized.

It is important to recognize that these qualities are achieved in Lewerentz’s design entirely through the tectonic fabric of the architecture – that is, by the (conventional) working of geometry, space, contour, form, materials, connections and light – rather than by overt representational, iconographic or other explicit religious signs and references; or indeed by any (radical) volumetric innovation. The semantic dimension of the architecture is delivered by its physical constitution and presence, rendered open and available to experience and interpretation. The coincidence of tectonics and meaning is construed here through consilient discrepancy between multiple unaligned systems, whose conjugational potential is calibrated to the metaphysical, philosophical, ethical, religious and aesthetic dimensions of Christian worship. These systems are overlaid in oppositional patterns – fundamentally undecidable and incommensurable – to produce a barely perceptive yet affective shuddering or shimmering of the architectural fabric. This in turn affords an experience of the awry, an enigmatic and simultaneous presence and absence of divinity; the insistent gravity, weight and simultaneous reconstitution of the material world; and the discomfiture, grief and simultaneous joy in noticing that the destiny of human being is an irremediable state of suspension between abandonment and recuperation, oblivion and solicitude.

Notes

Christian Classics Ethereal Library. ‘Creeds of Christendom, with a History and Critical Notes, Volume II. The History of Creeds’, http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/creeds2.iv.i.i.i.html (retrieved 26 February 2018).

See Giorgio Agamben, Profanations, trans. Jeff Fort (New York: Zone Books, 2007); and Jacques Derrida, The Beast and the Sovereign, Volume I, trans. Geoffrey Bennington (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2009).

The etymon is *SEQ, which produces a complex double network of sense – on the one hand, divisional: section, segment, segregate, secateurs, secrete, and on the other connective: segue, sequel, sequence, secure, secret. *SEQ can be read as the reflexive pronoun se-, apart, aside + the etymon *KREI – sieve, separate, discriminate, cure, create. Every creation is founded on sequestration, and more so architecture, whose foundational gesture is the segregation or secreting of an inside over and above an abyssal, abandoned outside.

The word ‘awry’ is from the etymon *WER, turn, bend. The awry is the wry, crooked, skewed, distorted, twisted or deviant; a doubling of the surface, a turning inside-out that shows what is normally concealed, excluded or forgotten. The word ‘wonder’ is cognate – from *WEND, (to move by) winding, turning, weaving (wander, wend, go, move) + *TER, term, boundary, borderline: what makes the borderline turn (to reveal its outer face/side to the inner; and vice versa; to become other, alter ego ...). The awry and the abject are in that sense correlates – hence the uncanny affect that blends fascination and fright, admiration and dread, terror and veneration, awe and wonder.

Martin Heidegger, Pathmarks, trans. William McNeil (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 307.

Rudolf Otto, The Idea of the Holy: An Inquiry into the Non-Rational Factor in the Idea of the Divine and Its Relation to the Rational, trans. John W. Harvey (London: Oxford University Press, 1923), 13–24.

The lyrics are as follows: L’ho perduta, me meschina! Ah chi sa dove sarà? Non la trovo. L’ho perduta. Meschinella! E mia cugina? E il padron, cosa dirà? (I have lost it, woe is me! Ah, who knows where it is? I can’t find it. I have lost it. Miserable little me. And my cousin? And the boss, what will he say?).

I am indebted to my counterparts at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, David Larkin and Lewis Cornwell, who generously provided the musicological detail in what follows.

The following extends my previous analyses of this building and other precedents. See my Agencies of the Frame: Tectonic Strategies in Cinema and Architecture (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2010), 252–7, 305–9.

Raymond Williams, The Politics of Modernism: Against the New Conformists (London: Verso, 1993), 40.

Peter Blundell Jones, ‘Sigurd Lewerentz: Church of St Peter, Klippan, 1963-66’, arq: Architectural Research Quarterly 6, no. 2 (2002): 159–73.

Colin St John Wilson, ‘Sigurd Lewerentz: The Sacred Buildings and the Sacred Sites’, in Sigurd Lewerentz 1885-1975, ed. Nicola Flora, Paola Giardiello and Gennaro Postiglione (Milan: Electa, 2001), 16, 21.

‘For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith – and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God – not by works, so that no one can boast’. Eph. 2. 8-9. Biblical citations are from the King James version available at http://www.gasl.org/refbib/Bible_King_James_V ersion.pdf (retrieved 23 February 2018).

1 Jn 1. 15.

1 Kgs 8. 12.

See Rene Guenon, ‘The Omphalos and Sacred Stones’, in The King of the World, trans. Henry D. Fohr (Hillsdale: Sophia Perennis, 2004), 54–61.