Meaning, variously, hand, mind and man

1/2

Seizure

A most evident provocation in the title `architecture by hand and mind' is the implied oppositional conjunction between making and thinking that architectural design is meant to reconcile. We are all familiar with this opposition—pitching practice against theory, concrete against abstract, practical against ideal, actual against virtual, and so on and on. But hand and mind are not opposed, antinomical or complementary. They are, at least linguistically if not practically, cognate. And this oppositional discrepancy—between practice and theory, between hand and mind—that design is charged with resolving is effectively an ill-founded, unsustainable setup.

Commonly the hand is taken as an extension or prosthesis of the mind—an apparatus or tool that implements, in the physical world, what the mind is incapable of doing by itself. Likewise, the mind is cast as motive and mobilizing force or impulse that activates and moves the hand, which is as such incapable of propulsion. Evidently an unmotivated hand is as ineffectual as an un-implementable mind devoid of a way or mechanism for action. Once the duality is established, we then look for evidence of seamless connection between the two. Nothing is more monstrous than a maniacal limb. But these instrumentalist metaphors are altogether too neat and too convenient. Language and practice tell us the reality is more complex, more ambiguous.

The word hand is from Old English hond, the human hand; also a side, part, direction, `handedness' (even or rough, left or right), as well as an executive capacity, that of `handling.' The sense of power, control and possession is implied in the hand's ability to grasp and grab—and there is an extensive lexicon around notions of calculated reach and forcible seizure, which give to the hand, or to the idea of the hand, its normative instrumental, appropriative tenor.

And yet, grasp, grip and grab derive from the Indogermanic ghrebh, to seize—found, most instructively, in the Sanscrit architectural term garbhagriha: the central space of the Vedic Altar, and later the central cell or sanctuary of the Hindu Temple. Garbhagriha literally means womb (garbha) chamber (griha). Alain Danielou defines it as the `dwelling of the (Golden) Embryo' or seed-house.[3] Here we have a direct lineage between the notion of grasping and that of a sheltering, spatial interiority: incavated space held, as it were, within the curving hollow cupping of a hand.

Jacques Derrida, glossing Martin Heidegger's metaphor of the hand as more than an appropriative instrument, writes:

"The hand's being (das Wesen der Hand) does not let itself be determined as a bodily organ of gripping (als ein leibliches Greiforgan). It is not an organic part of the body intended [destinée] for grasping, taking hold [prendre], indeed for scratching, let us add even for catching on [prendre], comprehending, conceiving... If there is a thought of the hand or a hand of thought, as Heidegger gives us to think, it is not of the order of conceptual grasping. Rather this thought of the hand belongs to the essence of the gift, of a giving that would give, if this is possible, without taking hold of anything. If the hand is also, no one can deny this, an organ for gripping (Greiforgan), that is not its essence, is not the hand's essence in the human being."[4]

Here is architecture's foundational gesture, how it plays its hand—sequestration of an inside, secreted and dark, from an outside, evident and bright; both terms produced simultaneously, joined and separated by an occluding boundary—and what it hands out or hands over. In other words, what it gives.

3/4

Gift

We have to take account of the multiple senses of giving: generous, punitive; pleasurable, painful; the gift given without reserve, without the call to respond in kind or otherwise; the gift given in view of the ban, bond, bondage or the deal and the contract, entailing binding exchange and intricate responsibility, duty, accountability and reconciliation. Every gift comes at a cost. Design, if it is a gift as we like to think, always comports installation and establishment (of a world, system, site, framework, building...), and therefore appropriation (of a territory, people, culture, language, materials...). Design always takes, always seizes; and is itself a kind of seizure of indefinite possibilities reduced, by decision, to a decisive singularity. And design always gives, always releases; more or less efficaciously, more or less generously. Because de-sign is, literally, signaling-out, signifying and signing-off. It indicates and releases, retains and consigns. Likewise, while the key gesture of seizure is appropriation, taking and collecting is always accompanied by a parallel gesture of gathering and welcoming, situating and making-place, protecting and safeguarding. This was the double sense of Old Norse mund, Greek mane, Latin manus, around the etymon *MAN—meaning, variously, hand, man and mind.

5/6

Man-

The etymon *MAN is particularly rich and gives rise to a complex lexicon around five related ideas: 1. abiding or remaining (manor, manse, mansion, ménage, menial, immanence, permanence, remainder...); 2. remembering and thinking (admonish, amnesia, commemoration, comment, dement, demonstrate, mania, memento, mental, mention, mentor, mind, mnemonic, Mnemosyne, money, remembrance, reminiscence...); 3. projecting (amount, demeanor, eminence, mane, menace, monster, monstration, montage, mount, mountain, mouth, promenade, prominence, promontory, surmount...); 4. measuring (meniscus, mensual, mensuration, Monday, money, month, moon, dimension, immense,...) and 5. making (demand, command, emancipate, maintain, manage, mandate, maneuver, manifest, manipulate, manner, manual, manufacture, manuscript, recommend, remand...).

This prompts us to consider `man'—human being—as that one who abides and stays (put), who remembers and thinks, who projects and designs, who measures and who makes: a manipulative, mental being who, by skillful handling and maneuver, indicates, evidences, makes apparent and apprehensible, manufactures, manifests and produces, discovers, shows and demonstrates what is already there as well as what is not yet there. Such productive disclosure has two registers: revelation and betrayal—on the one hand giving and on the other, by giving such and such, foreclosing the potentiality of what might have been (given, handed over); what Derrida calls the "precariousness of that opposition of the gift and of the grip, of the gift that presents and the gift that grips or holds or takes back."[5]

7/8

Monster

In a reference to Hoelderlin's Mnemosyne, Martin Heidegger brings together three motifs—the hand, the gift and the sign:

"The hand reaches and extends, receives and welcomes—and not just things: the hand extends itself, and receives its own welcome in the hand of the other. The hand keeps. The hand carries. The hand designs and signs, presumably because man is a sign (Die Hand zeichnet, vermutlich weil der Mensch ein Zeichen ist)."[6]

Man is the signifier, the sign maker, the de-signer. In his gloss on this text, Derrida's parallel reading of German Zeigen (sign), Zeignung (signature), Zeigens (showing) and die Sage (the said), leads him to venture, as the distinguishing character of human being, monstration, demonstration, indication and pointing out by way of warning and putting on guard:

"The hand is monstrasity (monstosité), the proper of man as the being of monstration. This distinguishes him from every other Geschlecht [species, gender, type, generation] and above all from the ape."[7]

Consequently, for Derrida, "the hand cannot be spoken about without speaking of technics."[8] This is why Heidegger aligns thinking to manual production and craft, to the handywork of the cabinetmaker and joiner - the artificer who, attending to form and materials, assembles, articulates and connects. In one sense, this is in recognition of the actual work of manufacture; in another, that "the hand is in danger," that handywork mobilizes a counterpoint to the debasing influence of industrialized, machinic manufacture threatening both thinking and artisanal production, or thinking as artisanal production.[9]

Heidegger is explicit about the relation between hand and mind:

"the hand's gestures run everywhere through language, in their most perfect purity precisely when man speaks by being silent. And only when man speaks, does he thinknot the other way around, as metaphysics still believes. Every motion of the hand in every one of its works carries itself through the element of thinking, every bearing of the hand bears itself in that element. All the work of the hand is rooted in thinking. Therefor thinking (das Denken) itself is man's simplest, and for that reason hardest, Hand-Werk, if it would be properly accomplished."[10]

Derrida continues:

"The nerve of the argument seems to me reducible to the assured opposition of giving and taking: man's hand gives and gives itself, gives and is given, like thought or like what gives itself to be thought and what we do not yet think, whereas the organ of the ape or of man as a simple animal, indeed as an animal rationale, can only take hold of, grasp, lay hands on the thing. The organ can only take hold of and manipulate the thing insofar as, in any case, it does not have to deal with the thing as such, does not let the thing be in its essence."[11]

9/10

Evolution

In `The brain and the hand'—Chapter II of his Gesture and Speech—André Leroi-Gourhan cites Gregory of Nyssa from the Tractate on the Creation of Man (379 CE), where it is the hand that, through evolution of the human being, liberates speech—and not only speech, but an entire succession of liberations: the body in relation to water, the head in relation to earth, the hand in relation to locomotion and the brain in relation to the mask of the face.[12]

Leroi-Gourhan considers mobility as the significant human evolutionary trait. The hand is an organ of capture. Development to bilateral organization eventually leads to man. The animal world, since its beginnings, developed into a limited number of functional types; the choice being made, following compromise, between immobility and movement, between radial and bilateral symmetry—"the octopus and man marking the two extreme borderlines of adaptation." The evolution of vertebrates follows five stages, five liberations—from locomotion to cranial suspension, dentition, the hand "or at least the extremity of the anterior member in its possible integration with the technical field," and finally the brain as coordinating faculty of the entire corporeal apparatus (dispositif).[13] From an evolutionary perspective, the hand as organ of prehension (capture, defence) and the mouth as organ of alimentation are transformed into the hand as organ of giving/thinking/thanking and the mouth as organ of speech/language:

"The development of the apparatus of opposition of the fingers, more and more efficacious and precise, corresponds to a locomotion founded more and more on the prehensile preeminence of the hand in relation to the foot, to a sitting posture becoming more and more upright, to a contracting dentition, to manual operations of increasing complexity and a more and more developed brain."[14]

Consequently, Leroi-Gourhan argues that there is a close organic relation and coordination between the action of the hand and the frontal organs of the face in the capacity to formulate symbols of communication, to exercise language, gesture and speech as transcriptions or translations of the voice, moving from mouth to hand:

"The apparatus we have described forms the cortical framework for the modern human's speech. Neurological experiments have demonstrated that the zones of association that surround the motor cortex of the face and hand are jointly involved in producing phonetic or graphic symbols."[15]

Tools and language are neurologically linked and both are inseparable within the social structure of humanity. Hence technical progress is tied to the progress of technical symbols of language: itself, like architecture, a technical apparatus[16]—that is, in the Heideggerian sense, a mechanism for unconcealing, revealing and bringing to presence.[17]

11/12

Handshake

In the system of Pharaonic hieroglyphs, the hand signifies manifestation, action, donation and husbandry (that is, care and solicitude). It is associated with the pillar, as support and strength of an edifice.[18] The hieroglyph of the extended hand represents the verb, ‘to give.’ The act of shaking hands takes on symbolic significance in Babylonian and Greek iconography, where it represents the handing-over or transfer of power and authority from divinity to humanity. Handshaking—Greek dexiosis, Latin dextrarum iunctio, giving, joining of right hands, handclasp—intiates into the mysteries known as syndexioi (joined by the right hand), indicative of fidelity.

The multiple Hindu deities are commonly represented with multiple arms, symbolic of their extreme power (shakti) and reach; with each hand holding a particular object or implement—spear, thunderbolt, drum, shell—that enables that power to act efficaciously in the world.[19] There is then an extensive tradition of hand gestures typified by the Hasta (hand) Mudrã (seal) in Hindu and Buddhist theatre, dance, ritual and iconographic practices, where each of the five fingers represents an elemental quality and its corresponding sense (thumb/fire/sight, index/air/touch, middle/ether/hearing, ring/earth/smell, little/water/taste); and where the fingers, arranged in patterns and combinations, conjugate and mobilize those qualities. Mudrã is a language, but an executive language of gestures that eclipses instrumental communication by effectively acting on self and world.[20]

13/14

Pointing into the withdrawal

The conjunction hand + mind is characteristic of humans as grasping/indicating and thinking/speaking beings. Yet what is grasped and manifest by hand and mind, what is shown and shines forth, is not the apparent but the unapparent—what we are likely to have overlooked, missed or mistaken; what disappears in absenting itself. It is the give-and-take—or, in Heideggerian terms, the simultaneous appearance and disappearance, advancing and withdrawal, presence and absence—that characterizes what the hand indicates and what thought says:

"What must be thought about, turns away from man. It withdraws from him... Whatever withdraws refuses arrival... The event of withdrawal could be what is most present in all our present, and so infinitely exceeds the actuality of everything actual.... What withdraws from us draws us along by its very withdrawal... As we are drawing toward what withdraws, we ourselves are pointers pointing toward it. We are who we are by pointing in that direction... To the extent that man is drawing that way, he points toward what withdraws. As he is pointing that way, man is the pointer... drawn into what withdraws, drawing toward it and thus pointing into the withdrawal, man first is man. His essential nature lies in being such a pointer. Something which in itself, by its essential nature, is pointing, we call a sign. As he draws toward what withdraws, man is a sign. But since this sign points toward what draws away, it points, not so much at what draws away as into the withdrawal."[21]

We are not moving towards anything; rather, we are always-already in the midst of that towards which we appear to be moving. We are the movement itself, the movement of the to-ward itself. There is no destination; only destining as the place in which we move and of which we are the motion and the motive.

We can see now the relevance of Sanscrit garbhagriha and the architectural sanctuary as cave within mountain, gape or chasm within mass, absence within presence—indeed of an excavation ready to receive a corpse: the presence of a disappearance. Garbhagriha has its Indogermanic counterpart in graban (Anglosaxon graf, Old High German grab, grave, tomb; Gothic graba, ditch; Norse grafa and Dutch graven, to dig, delve, inquire into) and the etymon *GHREBH, dig, scratch, scrape, carve, graft—that is, drawing as in-scription (marking-into), de-scription (marking-out) and ex-scription (marking-away/beyond); drawing as naming, signature and the production of graven images (that are false, counterfeit, hence errant and betraying); and drawing as (de)monstration and creation.[22] In fact, the sense of manifestation as creation (that is, as craft in the German sense of kraft, meaning power, strength, skill, dexterity) is evident in the latter's etymon: *KER, horn, head, projection—and by extension, to grow, increase, bring forth, produce, beget, arise. A further extensive lexicon accrues: concrete, corn, corner, cranium, create, crescent, crest, excrescence, increase...[23]

In any case, design is always a species of cutting—whether cutting or foregrounding a figure over against a (back)ground, cutting one portion of space from another, cutting the earth to appropriate territory and install a foundation; or indeed by kerfing—that is, a technics of carpentry, cutting a series of grooves in timber to curve it. De-signing always signals, de-signates and signs-off by excision and projection—by creating worlds and things that are distinct, disaggregated entities with disseveral lives. A foundational notion emerges here of designed space—that is, of place—as constituted of a deliberative curving in the fabric of space which turns and folds it into itself so as to form the contours of a hollow—an inhabitable, sheltering enclosure.

Of course in-, de- and ex-scription move within the gamut of writing (Greek graphein, to scratch [on clay tablets, with a stylus]) and recording—hence within technologies and apparatuses of memorialization: charcoal and chalk, hammer and chisel, pen and paper, diagrams, drawings and texts, typewriters and computers, books, photographs, films, sound recordings, repositories, archives and libraries, buildings and ruins, landscapes, tailings, gravestones, glacial striations, shell middens, fish traps, scars, stains, wrinkles, folds...

Thinking, Heidegger says, is "something like building a cabinet. At any rate, it is a craft, a 'handicraft.' 'Craft' literally means the strength and skill in our hands..."[24] What sustains the cabinetmaker's craft—the technology allied to that craft—is "not the mere manipulation of tools, but the relatedness to wood... to such things as the shapes slumbering within wood."[25] Handywork, craft, are therefore not directed to grasping or gripping, but on the contrary to releasing: to letting lose or letting go of those "shapes slumbering within the wood"—a distinctly Platonic reading of latent eidos or idea that design is meant to liberate from uncivilized matter.

This liberation of unmanifest potential or unexercised capacity is not "leaving behind," "losing" or abandoning into oblivion and forgetfulness. Rather, it entails a disposition of solicitude and care: that is, releasing something "into the freedom of its own essential substance—and so leave it at the place where it by its nature belongs."[26] For Heidegger, this is the task of thinking—an ethical practice, a matter of "thanking"[27]; but it is equally a foundational task for architecture.

15/16

Beholden

In characterizing the human as "that being who has his being by pointing to what is,"[28] Heidegger highlights the tight connection—around aletheia (unconcealedness or truth)—between noesis (apprehension, cognate with gnosis, knowledge) and logos (name, speak, say, gather), between noein and legein—that is, between "letting lie there before us" and thus bringing to appearance or rendering visible, and perception and reception of what is made to appear[29]:

"The veiled nature of legein [letting-lie-before-us] and noein [taking-to-heart] lies in this, that they correspond to the unconcealed and its unconcealedness... Noein, taking-to-heart, is determined by legein. This means two things: first, noein unfolds out of legein. Taking is not grasping, but letting come what lies before us... Thinking, then, is not a grasping, neither the grasp of what lies before us, nor an attack upon it. In legein and noein, what lies before us is not manipulated by means of grasping. Thinking is not grasping or prehending."[30]

Elsewhere, Heidegger foregrounds the calculative over against the solicitous in terms of the look and the gaze. He distinguishes between a looking “which makes presence possible... (and) at the same time shelters and hides something undisclosed,” and “the look of a being that advances by calculating, i.e., by conquering, outwitting and attacking... the look of the predatory animal: glaring... But the basic feature of this grasping look is not glaring, by means of which beings are, so to say, impaled and become in this way first and foremost objects of conquest.”[31] The call is for a kind of looking that does not grab and 'lock' onto a subject in order to incarcerate or eliminate it by defining it. On the contrary, this looking proceeds by way of attentiveness and care towards the arrival of whatever manifests itself in a given situation. It is not a matter of closing down but of unlocking and releasing.

To grasp, to indicate, to make perceptible or bring into presence, to design: these are all instances of naming, of giving indices, of indexing—and hence of teaching (the common etymon is *DEIK, to show). "Naming is a kind of calling," says Heidegger,[32] a kind of gathering, an offer of abode—that is, siting and situating: an ethical practice of making place (for) something to come into its own, to be itself. What arrives might be something like civic life in a public domain designed for the emergence of transactive civil society. It might be the arrival of a particular spatiality—the cinematic for example, or the ceremonial; or a particular temporality, the solstice for example, the long while of vacation, or the gloaming at twilight. Design is this kind of beholding: not merely bringing something into view (into existence), or fixing and gazing upon it, but rather watching and attending to its arrival. Design produces the conditions and the sites that enable this to happen; it puts in place the infrastructure for place to take place. What arrives there, in the midst, might be the place itself—architecture framing an attunement to context in such a way as to indicate that place more precisely, to amplify and magnify it, to disclose and show it, to let it be seen as if for the first time.

Notes

[1] George Orwell, Animal Farm (Melbourne: The Text Publishing Company, 2017), 33.

[2] Martin Heidegger, What is Called Thinking, trans. J. Glenn Grey (New York: Harper & Row, 1968), 16.

[3] Alain Danielou, The Hindu Temple: Deification of Eroticism, trans. Ken Hurry (Rochester: Inner Traditions, 2001), 49-54.

[4] Jacques Derrida, "Geschlecht II: Heidegger's hand," in Deconstruction and Philosophy: the Texts of Jacques Derrida, ed. John Salis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 172-3.

[5] Derrida, Geschlecht II, 176.

[6] Heidegger, What is Called Thinking, 16.

[7] Derrida, Geschlecht II, 169. Notable here is the connection between the gesture of indicating (the index finger of the hand), the indicative sign or signifier, the index or signature of both gesture and sign, and the saying or speech. The common etymon is *DEIK, to show, teach, pronounce. Instructive are motifs such as the monstrous hand and the severed hand in Victorian literature. See Kimberly Cox, "The Hand and the mind, the man and the monster," Victorian Network 7, no. 1 (Summer 2016): 107: "Monstrosity and humanity overlap in monstrous hands that parallel monstrous minds." Here the hand itself becomes a sign of the constructed dichotomy between human and animal, man and beast. On this see Jacques Derrida, The Beast and the Sovereign (2 Volumes), trans. Geoffrey Bennington (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009 and 2011).

[8] Derrida, Geschlecht II, 169.

[9] Heidegger, What is Called Thinking, 14-15; Derrida, Geschlecht II, 172.

[10] Heidegger, What is Called Thinking, 16-17.

[11] Derrida, Geschlecht II, 175.

[12] André Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech, trans. Anna Bostock Berger (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 1993), 35-6; 25. See Kimberley Cox, "The hand and the mind," 107: "early nineteenth-century discourses on human exceptionalism suggested that the development of the human brain correlated with the evolution of the hand's dexterity and tactile sensitivity."

[13] Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech, 36-7.

[14] Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech, 42.

[15] Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech, 88.

[16] Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech, 114.

[17] Martin Heidegger, "The question concerning technology," in The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays, trans. William Lovitt (New York: Harper & Row, 1977), 3-35.

[18] Juan Eduardo Cirlot, A Dictionary of Symbols, trans. Jack Sage (London: Routledge, 2001), 137-8.

[19] See for example Kapila Vatsyayan, Classical Indian Dance in Literature and the Arts (New Delhi: Sangeet Natask Akademi, 1977).

[20] See for example Ananda K Coomaraswamy, The Mirror of Gesture (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 1977) and Denise Cush, Catherine Robinson and Michael York, eds., Encyclopedia of Hinduism (Abingdon: Routledge, 2008), 511: "According to Abhinavagupta, mudrã, mantra (diagram) and dhyãna (mental image) are the three essential features of tantric practice, corresponding to the body, speech and mind of both deity and practitioner. (Tantrãloka 15. 259)"

[21] Heidegger, What is Called Thinking, 9-10.

[22] Derrida foregrounds the link between hand, handiwork and handwriting or "manuscripture," of which engraving is a foundational mode. He notes that for Heidegger typewriting as machinic copy "degrades" "the word or the speech it reduces to a simple means of transport, to the instrument of commerce and communication." Derrida, Geschlecht II, 179. It is worth developing the alliance between Grundriss ([architectural] plan: literally `ground-rift' or `ground-trait'; that is, architecture as inscription and violation of the earth—from Grund, ground and Riss, crack, fissure, split, tear, breach, rift; initially from the etymon *Rei, scratch, cut) and cognate words related to the function of the hand—engraving, mark-making and indicating: Zeichnung, signature; Zeichen, sign (monstrosity); what the hand shows, demonstrates; and Geschlecht, mark, remark.

[23] Worth mentioning here is the cognate word `crease' (ridge, scar), in the sense of a plait or fold—both raised and engraved; and the idea of the fold as a site of potentialization, intensification and magnification: a pivot of rhythmic transport equivalent to poetic enjambment and versification. Adrian Snodgrass and Richard Coyne develop an allied spatial notion in their treatment of Japanese Ma as `cut-continuance' in Interpretation in Architecture: Design as a way of Thinking (Abingdon: Routledge, 2006), 221-240.

[24] Heidegger, What is Called Thinking, 16.

[25] Heidegger, What is Called Thinking, 23.

[26] Heidegger, What is Called Thinking, 52.

[27] Heidegger, What is Called Thinking, 146.

[28] Heidegger, What is Called Thinking, 149.

[29] Heidegger, What is Called Thinking, 202-203.

[30] Heidegger, What is Called Thinking, 221.

[31] Heidegger, Parmenides, trans. Andre Schuwer and Richard Rojcewicz (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992), 108.

[32] Heidegger, What is Called Thinking, 124-125.

Bibliography

Cirlot, Juan Eduardo. A Dictionary of Symbols. Translated by Jack Sage. London: Routledge, 2001.

Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. The Mirror of Gesture. Harvard: Harvard University Press, 1977.

Cox, Kimberly. "The Hand and the Mind. The Man and the Monster." Victorian Network 7, no. 1 (Summer 2016): 107-136.

Cush, Denise, Catherine Robinson, and Michael York, eds. Encyclopedia of Hinduism Abingdon: Routledge, 2008.

Danielou, Alain. The Hindu Temple: Deification of Eroticism. Translated by Ken Hurry. Rochester: Inner Traditions, 2001.

Derrida, Jacques. "Geschlecht II: Heidegger's hand." In Deconstruction and Philosophy: the Texts of Jacques Derrida, edited by John Salis, 172-3. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

—The Beast and the Sovereign (2 Volumes). Translated by Geoffrey Bennington. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009 and 2011.

Heidegger, Martin. Parmenides. Translated by Andre Schuwer and Richard Rojcewicz. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992.

—"The question concerning technology," in The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays. Translated by William Lovitt. New York: Harper & Row, 1977, 3-35.

—What is Called Thinking. Translated by J. Glenn Grey. New York: Harper & Row, 1968.

Leroi-Gourhan, André. Gesture and Speech. Translated by Anna Bostock Berger. Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 1993.

Orwell, George. Animal Farm. Melbourne: The Text Publishing Company, 2017.

Snodgrass, Adrian and Richard Coyne. Interpretation in Architecture: Design as a way of Thinking. Abingdon: Routledge, 2006.

Vatsyayan, Kapila. Classical Indian Dance in Literature and the Arts. New Delhi: Sangeet Natask Akademi, 1977.

Images

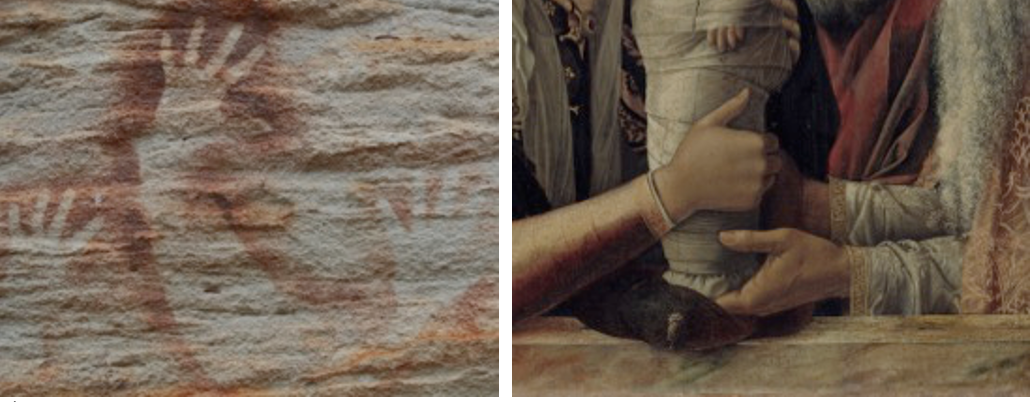

1. Qinkan Rock Art, Split Rock, Queensland (Michael Tawa, 2016)

2. Andrea Mantegna, Presentation in the Temple (c1465), Bpk/Gemäldegalerie, SMB/Jörg P. Anders

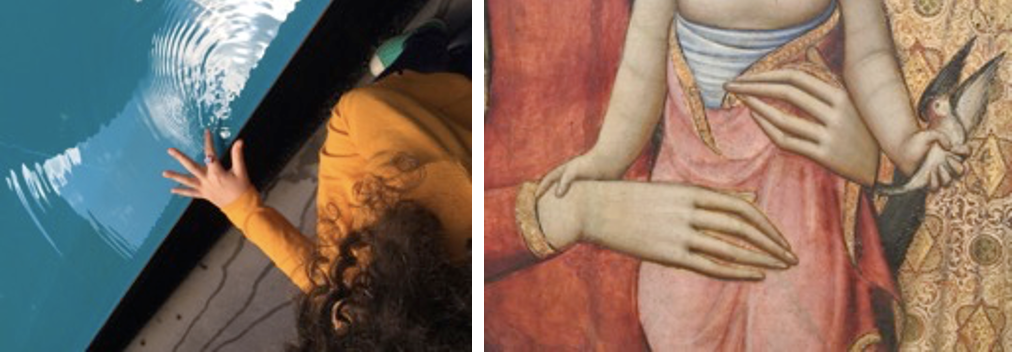

3. Patjarr, Western Australia (Michael Tawa, 2000)

4. Dutch School, A Man and his Wife (1549), © The Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge

5. Lyn Rin Masuda, Taxonomy Rain, Venice Biennale Of Architecture (Michael Tawa, 2016)

6. Gentile Bellini, Virgin and Child (c1460), Bpk/Gemäldegalerie, SMB/Jörg P. Anders

7. Amalia (Michael Tawa, 2012)

8. Niccolà Di Pietro Gerini, Virgin And Child (14thc), © The Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge

9. Lymesmith (Michael Tawa, 2015)

10. Neroccio di Bartolommeo de Landi, Virgin And Child With St Bernadino and St Catherine of Siena (1447-1500), © The Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge

11. Hands (Michael Tawa, 2015)

12. Giovanni Bellini, Virgin and Child (c1430), Bpk/Gemäldegalerie, SMB/Jörg P. Anders

13. Amalia (Michael Tawa, 2015)

14. Luca di Tomme, Virgin And Child Enthroned (1367-1370), © The Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge

15. Lunch, Sydney (Michael Tawa, 2015)

16. Andrea di Niccolà di Giacomo, Virgin And Child Between St Jerome And St Peter (15thC), © The Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge