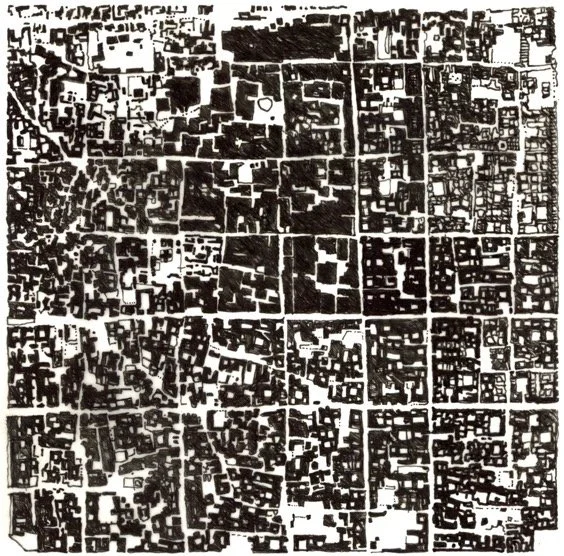

Dense City

Density

1. Density. Drawing by Michael Tawa. 1992.

Dense city is a tautology. The word `dense' is from Latin densus, and the etymons *DENS, thick; *TEN, stretched, tight, in state of (nervous) tension, intense, highly-strung; and *TENK, to become firm, curdle, thicken. The sense is of something taught and under force of compaction; or of something that has coagulated due to internal tension. The motif is resolutely spatial and pivots on notions of the solid and the sedentary. The word `city' derives from the etymon *SED—Latin sedere, Old English sittan—to sit, settle, stay, remain. The city is a cipher of stasis, of settlement, of statism—with all that that implies: appropriation of territory, delineation of borderlines, exclusion, agriculture, cultivation, domestication, civilisation, culture.

Topos

2. Topos. Drawing by Michel Tawa. 2000.

We have many names for the city: Greek polis (political, police, policy, polity, people, polite), Latin urbs (urban), French cité (citadel, citizen, civic, civil, civility). Evidently there is conjunction between the formal, concrete presence of a constructed environment and the life that takes place there: that is, a conjunction between a collective tectonic composition, situated and localised in space (topos) and an ethical disposition (ethos); a being-there, and a manner of being-with, regulated by established norms (logos) that bind collectivity and place. In architecture as in music, the Greek orders have both aesthetic/modal/tectonic (Doric, Ionic) and moral (Dorian, Ionian) registers. What we build is foundationally conditioned by where we are (from) and how we are (together) in a given place, in a circumstance, according to a circumambiance. The conjunction logos/topos/ethos that characterises Western civil society at its origins finds a surprising resonance in First Nations concepts of Country.

Polis

3. Polis: rue Sultan Hussein, Alexandria. Drawing by Michael Tawa. 2000.

The ancient Greek state, the polis, is a citadel—an acropolis (a high city that rises sharply); a community of citizens (politeia) and a civil administration or system of governance (policy, police). Polis is itself subject to a dense semantic. The etymon of the word is *PEL, which can be read in three related senses: 1. in terms of something folded, furled, plaited, felted, wrapped and filled-up so that its texture becomes intensified, complicated, compressed and thickened—like felt, fulled and matted by beating; 2. in terms of what is impelled, driven, shaken-up and made to tremble; 3. in terms of what expels, catapults, pullulates, multiplies profusely, sprouts or comes-forth and produces. The city is a site of pullulation; of profuse production. Its citizens are hoi polloi—the people—as a plethora, a great multitude of incessant industry, activity and noise. Wealth—Greek plouos (compare French pluie, rain and pleurer, to cry—as the pluvial release of a supersaturated state of condensation and emotion respectively)—is produced there in abundance, repletion and plenitude.

The Latin urbs is more difficult to align with this semantic constellation. Urbanus means pertaining to city life; to the city dweller. Urbis is a walled town—itself a tautology since `town' derives from Old English/Old Saxon tun, enclosure, garden, field, yard, homestead; group of houses, village; fence, hedge; Proto-Germanic tunaz, fortified place; Celtic dunon, hill-fort. These are all from the etymon *DHU-NO, enclosed, fortified place; *DHEUE, to close, finish, come full circle; cognate with English `down,' from Old English dun, hill, moor, dune, sand bank. For its part, the `village'—also a conjunction of constructed place and culture— is cognate, deriving from French ville, and the etymon *WEIK, clan, social unit above the household (Greek oikos, house; Latin vicus, village, group of houses). The sustained meaning seems to pivot on the idea of a boundary delineating a collectivity—human and constructed; possibly circular in form if urbs can be linked to Latin orbis—circle, disc, ring, orb, sphere, glove. But the etymon of urbs is *KWERP, to turn(over), revolve, stir (up), cause busy activity (cognate with Old English hweorfan, to turn, whirl); and so the urban might be read in similar terms to the polis, as a site—like the wharf of a busy port—again, pullulating and teeming with industry. Likewise, if we read *DHU-NO in relation to *DWEN—to make noise, sound, resound, cause a disturbance, uproar, brawl—we again have this sense of the city as a site of radical commotion.

The word `city' is particularly instructive. The Latin is civitas, citizenship, rights of a citizen, membership of a community; with the meaning eventually transferred from the inhabitants to the place. The Latin for city is urbs, but a citizen of the urbs is a civis. Civilis means pertaining to a society, public life, civility and good citizenship. Implied here, of course, is a counterpoint: the barbarous. Civil society is civilised, it behaves in accordance with civil law and the rules of the state. Civil society is also civilising, it seeks to appropriate and bind territory to itself, thereby producing the two oppositional terms of a very familiar dichotomy: human over against animal, civilization over against barbarity, the cooked over against the raw, law over against the lawless, city over against country.

Living in accordance with civil law, in conformity to policy, as a member of the polity, is to behave politely. This too is instructive. The polite is polished, burnished. From the Latin politus, it means rendered elegant and refined by smoothing-out (polire), decorating and embellishing. But these terms also derive from *PLE, the fulling of cloth by striking, beating and matting—that is, imbricating, homogenising; or, in the Old Testament sense of civilising the earth by pummeling it: “Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make straight in the desert a highway for our God. Every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill shall be made low: and the crooked shall be made straight, and the rough places plain.”[1] William Blake's rejoinder is edifying: "Improvement makes straight roads, but the crooked roads without Improvement, are roads of Genius."[2] Significantly, the word `courtesy'—at first blush a moral term—conjoins ethics and space. To be courteous is to display courtly bearing or manners; but courtesy is cognate with `court,' derives from the common etymon *GHER, grasp, enclose (Sanskrit ghra, house; Greek khortos, pasture; Old English geard, fenced enclosure, yard, garden, orchard), and is explicitly associated with the city as binding curtilage and girded region (Russian grad, Slavonic gradu, town, city).

Cleft

4. Cleft. Drawing by Michael Tawa. 1988.

Here we encounter a foundation trope: country (Old French contrée, Latin contrata) is originarily conceptualised as what stands opposite and over-against the city, what counters it, what is contrary to it. Yet country is also what makes the city possible. The city sits; casts and settled over against the unsettled, the rule of law over against sedition, sedentarism over against nomadism—for it was, allegorically if not concretely, that Cain, the first city builder and agriculturalist, whose fratricide of Abel, the stockman and nomad, set the city on its catastrophic course of sedition against the earth.[3] A cipher of civilisation, the city stands in opposition to nature; and yet the city only exists on account of the land and the waters, the forests and the mountains—in other words, of the Country—that, following Heidegger's reading of technology as enframing, it sets up as standing reserve, as undepletable resources for appropriation and capitalisation.

Incavation

5. Incavation. Drawing by Michael Tawa. 1988.

Returning to the etymon *PEL, and the idea of the city as a folded and felted contexture, the idea of density has to be read coextensively. The city is densification, and its density is a matter of imbricated concatenation, cloudiness or turbidity. Latin densus means thick, crowded—here again we have this notion of an excessively populated region whose texture darkens and intensifies. Density is cognate with tension, through the etymon *TEN, Latin tendere, to stretch (tight), extend, measure-out—to be in a state of nervous tension: that of hoi polloi; the intensity of a felted tectonic contexture. Important here is the allied sense of temporality. *TEN refers to time—Latin tempus, time; French tens, era, occasion, opportunity, verbal tense; and temps, weather, season, climate: the later from *KLEI, to lean (Greek klima, Latin clinamen)—that is, inclination, tendency (towards), intension. In that regard, the city is a conjugated setting such that its density is taken to a state of supersaturation and imminent crisis; to that radically temporary, seditional threshold of opportunity the Greeks called kairos, to distinguish it from khronos, chronological time. The city is a construal of opportunity.

Porosity

6. Plan of Jaipur. Figure-ground drawing by Michael Tawa, after Vidyadhar. City Plan of Jaipur. Jaipur State, Undivided India, 1734. Vastu Shilpa Foundation/Vivek Nanda.

But density must admit of porosity; and compaction of dilation. The density of the city is porous; its texture labyrinthine—otherwise it could afford no possibility of tarrying, remaining, settling, living or breathing. Its felted materiality must be riddled with hollows and voids, perforations and interstices. It must enable peregrination, wandering, disorientation and deterritorialisation. By definition, the porous gives access. Latin poros means pore, passageway—from the etymon *PER, forward, in front of, forth, through (Greek poros, journey; peirein, pierce, pass through; Latin portare, carry; porta, gate, door; portus, port, harbour; peritus, experienced; experiri, try; periculum, peril, danger). Passage is always a trial and always comes at some risk—on the one hand the risk of death and loss (of what one leaves behind), and on the other of losing oneself in the intricacies of what the porous opens up in the fabric of a contexture: whether a philosophy, a landscape, a building or a city. What is without pore is an impasse, an entrapment. It offers no way through, no passage, no relay, no transectionality, no transactionality. Everywhere is blockage, prohibition, injunction, ban. And such is the contradictory, ambiguous condition of the dysfunctional city: on the one hand excessive virtual connectivity, on the other radical aporesis, perplexity and existential entrapment (extreme privatisation, impaired infrastructures, interminable reconstruction, intractable bottlenecks, industrial dint, premeditated inhospitality, uncivilised cheerlessness, hostility, rage...).

Improvisation

7. City exercise. Drawing by Michael Tawa. 1998.

We owe to Walter Benjamin and Asjas Lascis a reading of the city of Naples that foregrounds its perforate texture and the critical role and value of the "dispersed, porous, commingled" to a convivial setting for cultivated human life:[4]

"The city is craggy. Seen from a height not reached by the cries from below, from the Castell San Martino, it lies deserted in the dusk, grown into the rock. Only a strip of shore runs level; behind the buildings rise in tiers. Tenement blocks of six or seven stories, with staircases climbing their foundations, appear against the villas as skyscrapers. At the base of the cliff itself, where it touches the shore, caves have been hewn. As in the hermit pictures of the Trecento, a door is seen here and there in the rock. If it is open one can see into large cellars, which are at the same time sleeping places and storehouses. Farther on steps lead down to the sea, to fishermen’s taverns installed in natural grottoes. Dim light and thin music come up from them in the evening. As porous as this stone is the architecture. Building and action interpenetrate in the courtyards, arcades, and stairways. In everything they preserve the scope to become a theater of new, unforeseen constellations. The stamp of the definitive is avoided. No situation appears intended forever, no figure asserts its 'thus and not otherwise.' This is how architecture, the most binding of all communal rhythm, come into being here: civilized, private, and ordered only in the great hotel and warehouse buildings on the quays; anarchical, embroiled, village-like in the center, into which large networks of streets were hacked only forty years ago."

This also means that urban contexture, as a porous field, must preserve a dimension of multivalency, incompleteness and unactualised potentiality. It must avoid the "stamp of the definitive" so as to render it available and open to interpretation and interminable reinvention, to adventure, to advent and to eventuation. The means of doing this, by design—that is, of designing for potentiality, for infinite finishing, for a city that is systematically in-completion: Benjamin and Lascis' "passion for improvisation"—constitutes the urgent challenge of the future city.

The city is planned, designed; or it develops by sedimentation, incrementally. Either way, if it makes no room for the interstitial—for sliding between its boundaries, its limits, its internal logic and order, its protocols, its prohibitions—then density becomes incarcerating rather than liberating. But if that density is vesicular and leavened by pervasive incavation, then it affords access and preserves, for the citizen, the capacity to counteract, to challenge, to invent and to write with and/or against the grain. In pumice stone—a perfect analog—the pores are produced by trapped, exsolving bubbles of gas during rapid cooling and depressurisation of a highly aerated magma. The topology of pumice is an infinitely folded surface where inside and outside become indistinguishable and indeterminate. There is a world of difference between the dense urbanism of the premodern city, where porosity is tectonically evident and palpable, and the only apparent transparency and extensive accessibility of the contemporary conurbation, where porosity is radically virtualised, indefinitely refracted and resolutely a-tectonic. Here, porosity is a simulacrum; and access, radically privatised, under interminable surveillance and merely counterfeit.

In the drive to higher density and ubiquitous connurbation, some thought might be given to porosity and dilation as the other—necessary and enlivening—side of the city, according to which it makes possible civitas, politeia: that is, the urbane, convivial, civic and civil life of the body politic. For porosity also renders the city permeable, adaptable and resilient, casting it as an infrastructure for transactive and transitive cultural production.

References

Benjamin, Walter and Asja Lacis. "Naples," in Benjamin, Walter, Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings. Translated by Edmund Jephcott. New York/London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978 (1924): 163-73.

Blake, William. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: http://www.bartleby.com/235/253.html accessed 18 April 2018.

Vastu Shilpa Foundation/Vivek Nanda. Vidyadhar. City Plan of Jaipur. Jaipur State, Undivided India, 1734: https://architexturez.net/file/dr-s-0154-1-jpg-0 accessed 17 April 2018.

Footnotes

[1] Isaiah 40: 4.

[2] William Blake, "Proverbs of Hell," in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (c1790): 91, http://www.bartleby.com/235/253.html accessed 18 April 2018.

[3] Genesis 4: 16-17, " And Cain went out from the presence of the Lord, and dwelt in the land of Nod, on the east of Eden. And Cain knew his wife; and she conceived, and bare Enoch: and he builded a city, and called the name of the city, after the name of his son, Enoch." Enoch is from the Hebrew hanukkah, meaning dedicated, consecrated, commencement.

[4] Benjamin, Walter and Lacis, Asja. "Naples," in Benjamin, Walter, Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings. Translated by Edmund Jephcott. New York/London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978 (1924): 165-6.